An Idea of Sharing 2.

Public Opinion 3.

Nonspeculation 4.

Equity 5.

Debt 6.

Land 7.

Zoning 8.

The Competition

Introduction:

Housing and the Agency of Nonspeculation

Anne Kockelkorn & Susanne Schindler

Zurich is a center of global finance and exemplifies the associated pressure of a financialized real estate market on housing practices. Rents for new residential leases have risen by more than 60 percent since 2000, property prices have approximately doubled since 2009 and large-scale inner-city developments are today run by globalized financial investors and pension funds. At the same time, Switzerland’s largest and historically most industrialized city has not been subject to the same processes of social polarization and gentrification as Berlin or London. In fact, Zurich has a century-old tradition of nonprofit housing, a sector that has grown continuously since 1995. Today, 25 percent of the city’s dwelling units are permanently withdrawn from the for-profit sector, with the largest share, 18 percent, cooperatively owned and the remainder comprising municipal housing or housing operated by other nonprofit entities.

What makes the Zurich case so remarkable is not just the sustained commitment to decommodification. Cooperatives founded one hundred years ago offer city-center rents at one-third the market rate, demonstrating the “collective possibility” of architecture and urban design—a powerful conceptual counterpoint to the myth of the autonomous individual. In the process of maintaining and expanding Zurich’s noncommodified housing stock, the city’s cooperative movement—activists, city officials, architects, funders—has supported and realized experimental forms of living together that are able to accommodate and incite social change. Emblematic projects of cooperative organizations such as Kraftwerk1, Kalkbreite and mehr als wohnen, realized from 1998 to 2015, cater to a variety of income groups and household formations. They also offer collective spaces of stunning architectural and material quality and contribute to a public realm of which multiple user groups, including the general public, can partake.

Photo: Anna Derriks

Zurich proves that architectural innovation and social entrepreneurship in housing—the simultaneity of social engagement and entrepreneurial action—is possible at scale, even in the age of real estate financialization. This striking case prompted us to ask: What enables a long-standing commitment to nonspeculation within a for-profit real estate market? How can Zurich’s cooperative model become transferrable to other places? How does architecture partake in these processes, and how does its partaking expand the definition of architecture?

1. Appraisal: Housing the Self, the Collective and the City

Resonance with the World

To appreciate what Zurich has achieved in one hundred years of nonspeculative housing, we must take stock of the forces that shape how we live today. This concerns in particular the continuous acceleration and multiplication of option imposed by the process of modernization and its antinomy to modernity’s promise of individual self-determination and autonomy. In most Western, industrialized countries, these forces are in tension with one another: individuals often feel torn, driven toward an individualism and entrepreneurial self-responsibility that precludes the collective, while struggling to maintain a sense of the good life to which they feel entitled.

In Society of Singularities (2017), sociologist Andreas Reckwitz observes that the notion of the “collective” is becoming increasingly charged with imaginaries of nationalism, racism and pejorative demarcations of sociocultural “losers.” At the same time, Reckwitz describes a broad societal striving (active since the 1970s) among the educated middle classes in the postindustrial societies of Western Europe to attain singularity; that is, the appreciation of a social entity in terms of “inherent complexity and inner density.” Today, Reckwitz argues, the individual’s performance of creativity and authenticity is what leads to societal attention and approval, and this striving must transcend anything related to the notion of a standardized mass society. But this singularization comes at a price. It pressures individuals to perform constant self-actualization in their professional and private lives, even as society’s accelerating rate of change increasingly limits any one individual’s chances of actually achieving singularization.

Chasing singularity and chasing the resources that seem necessary to achieve it can obscure the very goal that triggered the chase; namely, to live what Hartmut Rosa calls the “good life” based on the experience of a “positive resonance” between the self, others and the environment. Western societies increasingly confound the “good life” with the accumulation of resources—wealth, knowledge, networks, space—instead of defining and delimiting the conditions of positive resonance with the world.

Reckwitz’s and Rosa’s diagnoses help to explain why cooperatives are of interest: they offer an economic model that counters an otherwise unquestioned drive to maximize resources—including the unlimited appreciation of real estate values. Zurich’s cooperatives are also relevant because they reconcile the societal striving toward the singular with a notion of the collective that defies reactionary imaginaries of “the other.” They answer to the specific housing needs of an increasingly singularized society while offering the possibility of collectively sharing spaces, knowledge and resources at multiple scales of the city.

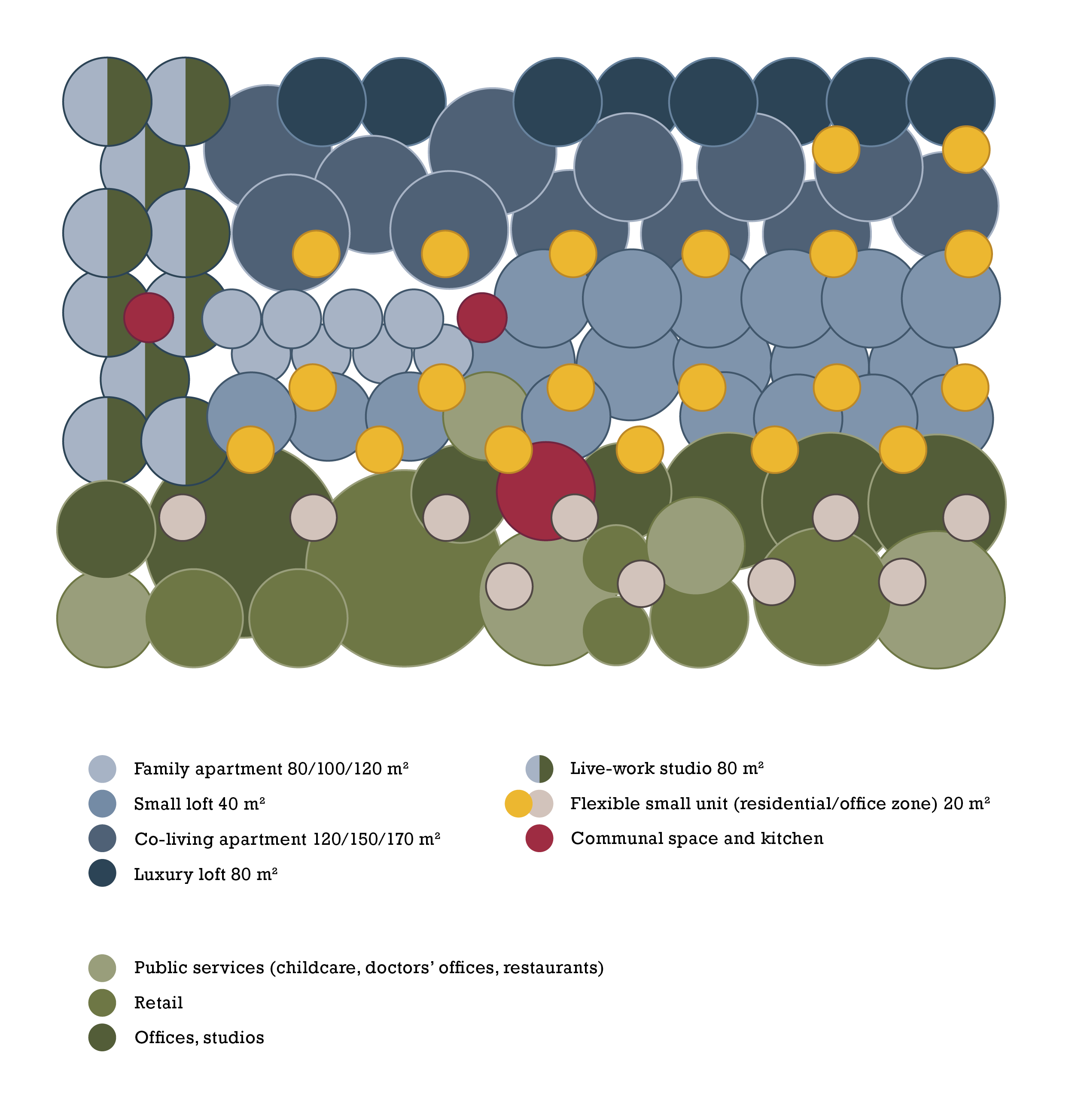

New Household Formations and Shared Spaces

At the scale of the household, the young cooperatives Kraftwerk1, Kalkbreite and mehr als wohnen have adopted a transitional understanding of “household,” asking who constitutes a social unit and for how long. Their apartment types embrace a patchwork of household configurations, from part-time families to solo dwellers, couples and the traditional “nuclear” family. Dwelling typologies include cluster housing—groups of micro-units assembled into a larger whole—as well as apartments for up to 50 people, sometimes with access to a serviced kitchen. Such exceptional apartment types are then combined with conventional flats to achieve a deliberately choreographed mix within a single development.

Cooperatives also offer a broad range of collectively shared spaces that allow these different household formations to live together. The ability to plan, build and maintain community facilities and shared urban spaces is a key characteristic of both new and old cooperative housing developments in Zurich: this ability evolved over the course of 100 years to compensate for strict occupancy rules (often allowing no more than one extra room per resident per dwelling) and reduced allocations of private space to each resident (one of the means by which cooperatives are able to offer cheaper rents than the for-profit market). “Our dwellings don’t stop at the front door,” says Philipp Klaus, a member of Kraftwerk1’s executive board. Shared spaces are therefore central to a cooperative’s mode of functioning, but the new generation of cooperatives has reframed their dimension and role. Kalkbreite, Zwicky Süd and House A at Hunziker Areal impress with light-flooded atrium stairwells, inviting laundry rooms, collective libraries, shared roof terraces and generous entry halls offering sheltered arrival for those pushing prams and carrying shopping bags.

Photo: Anna Derriks

At the scale of the neighborhood, cooperatives are expanding the use of shared space to include not only residents but neighbors and the wider public. This is of paramount importance when attempting to confer urban qualities on new developments in the urban periphery, and this is where the potential political and architectural economy of the cooperative is most relevant for the territorial equilibrium of cities today. Zwicky Süd and Hunziker Areal, both situated in underserved locations, have succeeded in creating urban micro-centralities by bringing small shops and other commercial enterprises to the ground floors of their development. Whereas private developers often refrain from implementing mixed-use in peripheral locations, cooperatives tend to be more successful because they are under less pressure to generate immediate revenue. As Anne Kaestle, principal of Duplex Architekten, master planners of Hunziker Areal, explains, this allows cooperatives to “curate” users and “take more time” to find suitable tenants.

Other large parcels on Zurich’s outskirts, cooperatives demonstrate a quieter but possibly more important variation of urbanity—one that offers shared experiences of urban spaces beyond those typically provided by commercial developments. In ABZ’s Entlisberg project, for example, balconies filter the private interiors toward landscaped areas that serve both as extensions of the surrounding apartments and as public walkways. These projects are, as Entlisberg’s architect Marius Hug, principal of Meier Hug Architekten, puts it, “machines for collective life” rather than Corbusian machines-for-living geared toward maximizing functional efficiency. This architecture offers public access to a shared experience of the urban on sites where such possibilities are anything but a given.

At the scale of the city, cooperative developments keep rents affordable for the lower and middle classes and protect residents’ right to remain for life—if not in a given apartment itself, then at least in the neighborhood. In contrast, residents of private developments generally pay higher rents, and this difference increases over time as the market value of land is figured into the for-profit rents, but not in the cost-rent of the cooperative developments. The projects of for-profit developers in Zurich also typically do not offer the broad scope of collective facilities and publicly accessible porous urban green spaces that cooperative developments do. Instead, their primary goal is to maximize financial revenue from privatized, marketable space. Urban space is first and foremost considered as a factor that increases the value of apartments and hence is preferably allocated to individual residents or the collective of residents—but not to the city.

These differing priorities become most obvious where cooperatives and for-profit developers have realized different sections of a larger development. At Glattpark, the space between the continuous building blocks of the for-profit developments consists of mowed lawns enclosed by hedges and produced for the gaze from the interior, while glazed balconies project the interior functions of dwelling toward the outside space. In contrast, the project by ABZ and pool Architekten offers publicly accessible walkways across a sequence of porous courtyards, with children’s playgrounds, bike racks and a landscaped public garden, while the receding loggias shelter residents on the upper floors from public view. But the absence of shared spaces in for-profit developments also indicates a knowledge gap: their developers know little about future users’ desires. Maintaining and managing shared facilities exceeds what they are willing and able to do.

The provision of outstanding material and socio-spatial qualities combined with the guarantee that they will remain exempt from commodification in perpetuity is possible because the Zurich model of cooperative housing privileges the use value of housing over its exchange value, or the commodity aspect of real estate. This notion of use value has been institutionalized in the municipal governance of urban space in Zurich for more than hundred years, and that is precisely what is so remarkable and forward-thinking about this case. Among the many regulatory instruments that allow for the positive resonance of Zurich’s cooperative housing today are privileged access to mortgages and the definition of Gemeinnützigkeit, which roughly translates as “nonprofit notion of the public interest.” These regulatory tools create what is called, in German, Handlungsspielraum, which best translates as “agency” but literally describes the space in which action becomes possible. The German term, by including Spiel, also implies a technical and theatrical notion of play and movement—notions that we think with when we refer to architecture’s agency in enabling a resonance with the world.

2. A Taxonomy of Conditions: Instruments, Origins, Agency

As part of our project, we offer a primer comprising eight dossiers—An Idea of Sharing, Public Opinion, Nonspeculation, Equity, Debt, Land, Zoning and The Competition—that systematically relate the regulatory conditions of cooperative housing to its concrete, socio-spatial materialization at the multiple scales of the city. By doing so, we are taking aim at the Handlungsspielraum, or agency of cooperative housing. This endeavor is based on two convictions. First, as architects and historians, we must expand the temporal framework of what constitutes the present and its possibilities for action by looking one hundred years into the past and future. Second, we must expand the understanding of architecture to include the socio-spatial relations that take place within the set of possibilities created by a regulatory framework.

This exercise in transversality and co-temporality builds on a substantial (and continuously increasing) body of scholarship both on cooperative housing in general and on Zurich’s housing cooperatives in particular. Exhaustive documentation by the Zurich city government has allowed researchers easy access to relevant data. Seminal histories of Zurich’s housing cooperatives allowed us to align with or contest existing interpretations of the past. Finally, we also build on a growing body of comparative studies of alternate development models as well as recent studies in the field of housing governmentality. In addition to this scholarship, Zurich’s cooperatives have become well known through exhibitions, magazines, journals and trade publications, as well as the cooperative organizations themselves, which actively encourage tours of their projects.

We expand this immense body of literature and the cooperatives’ own marketization efforts by situating cooperatives within financial systems, by showing how histories transform the future and by expanding understandings of architecture as built form. The goal of this approach is to counter an assumption, widely held in schools of architecture, that matters of architecture, finance and regulation are not, and should not be, part of the same field. Often, such arguments emerge from a fear of diminished disciplinary standing, as if economic literacy would undermine one’s credibility as a designer. Our approach also counters the separation between design courses and history and theory—not because history and theory should serve design in terms of the what or how but because they should empower designers to ask why.

Conditions and Instruments

To answer our project’s first question—What enables a commitment to nonspeculation within a for-profit real estate market?—we identified eight conditions that are essential to the emergence of cooperative housing in Zurich and its socio-spatial qualities. Each is elaborated in a website dossier that sets architectural form, social space, territorial regulation and the political economy of nonspeculation in relation to one another. For example, the first condition, An Idea of Sharing, not only impacts joint ownership and collective decision-making but also the disposition and use of shared spaces. The second condition, Public Opinion, is essential both for political support and the normalization of architectural typologies. The fourth and fifth conditions—Equity and Debt—relate cooperatives’ financial constructs to their organizational and architectural diversity. The conditions Land, Zoning and The Competition analyze how regulations pertaining to land-use and process, under the premise of nonspeculation, foster architectural and urban-design innovation. The key condition of our investigation—Nonspeculation—thus sits squarely between the regulatory, financial and spatial repercussions of the political economy of cooperative housing.

To get at the regulatory mechanics of these conditions, each dossier investigates two or three instruments of “territorial regulation” that describe the legal and societal framework of urban development through norms, rules, laws, conventions and other institutional relationships. The instruments answer fundamental questions at both the abstract and the concrete levels of government, such as the concept of Gemeinnützigkeit and “cost rent”. Instruments in other dossiers refer to concepts and practices that have become so naturalized that many practitioners rarely pause to question them; for instance, owning land or owing money. Some tools, such as “municipal rulings” or “the share” of a cooperative’s property are familiar to housing professionals but rarely investigated as triggers of urban design and architectural form. In turn, instruments well-known to architects and planners, such as zoning laws or competitions for land leases, explain how the abstract idea of sharing can be translated into concrete form.

Historic Origins and an Expanded Time Frame

To answer our second question—How can Zurich’s cooperative model become transferrable to other places?—we investigated the historic origins of conditions and instruments and considered them within an expanded time frame.

By focusing on the moment of emergence of a particular law or practice—how much equity is required to take out a loan or the way in which an architectural competition is organized—we can understand why a law or practice gained enough political support to become a reality. To whom and toward what end did it seem desirable? The social, economic and legal aspects of regulation are societal constructs: both negotiable and specific to a particular time and place. Thus, in seeking to make instruments transferable, one ought to focus not on transferring a law or practice from one place to another as is but on understanding the perceived promise of that law or practice at a particular moment in time.

To understand the relevance of such instruments today requires that they be considered within a longer-term historic continuity. Extending the time frame of analysis is particularly important for nonspeculative housing since its benefits, like low rent, accrue across time. And expanding the time frame is important not only for scholars who wish to study these effects. Crucially, practitioners must also consider the impact of their work not only in the five- to ten-year horizon that extends from idea to implementation but in a time frame that extends one hundred years into the past and one hundred into the future. An awareness of preceding generations’ struggles with similar challenges and how they responded can open new perspectives onto the how and why of one’s work. Similarly, reflecting on what present-day actions might mean one hundred years from now can productively reframe a design project. The point is to ask, with anthropologist Amanda Huron, how the benefits of the present extend beyond current beneficiaries toward “as yet unknown” future generations.

Such an expanded conceptualization of the present also allows us to resituate Zurich’s achievements in the context of Switzerland’s atypically high standard of living and political stability. This small, landlocked countryhas enjoyed remarkable longevity and thus trust in its institutions, disrupted neither by wars nor major social upheavals. Several circumstances have favored the emergence of cooperative practices: the political system is organized from the local to the national, and the sharing of limited natural resources has long been habitual. These aspects are hardly replicable. What can be transferred to other places, however, are the ways in which activists, citizens, elected officials, cooperative organizations and architects use legal, financial and regulatory instruments, as well as the architectural imagination, to advance a nonspeculative form of housing development and new forms of living together. The instruments we describe can be negotiated within the specific political struggles of other locales and will play out in a similar manner when deployed over time.

Agency and Handlungsspielraum

A response to the third guiding question of this project—How does architecture partake in these processes, and how does its partaking expand the definition of architecture?—becomes possible only through consideration of regulatory constructs, their historic origins and their long-standing impact on the built environment. The process of relating instruments and historic origins within a layered, condensed, yet expanded notion of time opens up architectural agency in a twofold way. The first is the agency of architects, planners and citizens to shape the built environment, to mediate social relations of living together and to bring about change through a range of strategies: it is the space in which action becomes possible, the Handlungsspielraum. The second notion of architectural agency refers to the effect of form itself, its Wirksamkeit. We argue that the use value of housing and the accessibility of desirable forms of living is not a matter of form alone, but a process that is directly tied to a regulatory framework and its ensuing urbanization processes. Hence, the agency of form is something that takes place in resonance with situated variations of use, the processes by which users’ selves are socially conditioned (i.e., subjectivation) and the ways territories and subjects are governed.

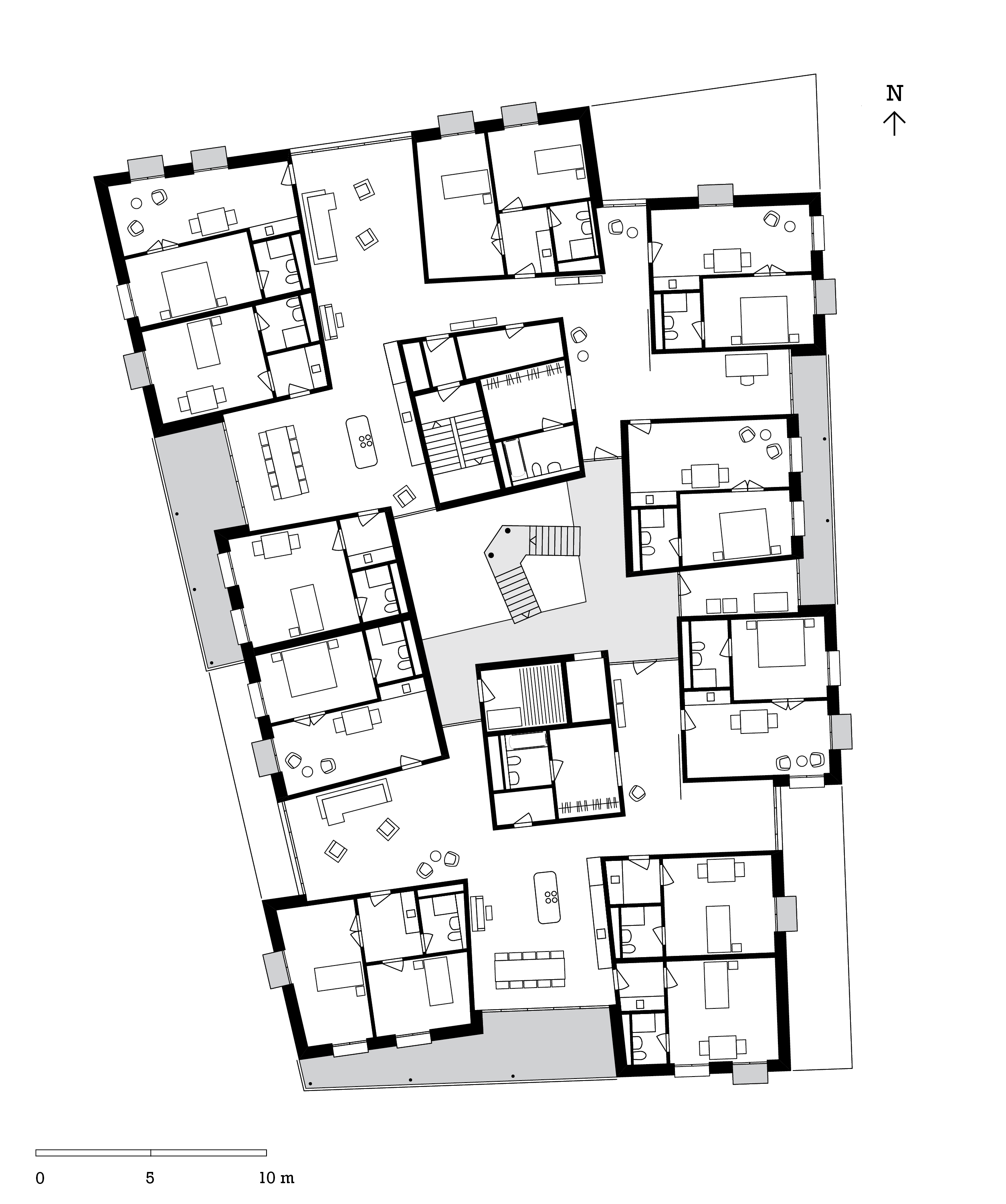

The floor plans for Zwicky Süd (2015), developed by a cooperative and two for-profit developers, exemplify how architectural agency involves such processes of subjectivation within a regulatory framework. Kraftwerk1, the cooperative developer, emphasized gallery access to its apartments and flexible, dividable floor plans, allowing residents to adapt their living environment as needed and encouraging spontaneous encounters among residents. The private developers, in contrast, prioritized point access and apartments with fixed, separate rooms, thus minimizing opportunities for encounters with neighbors and emphasizing privacy even within the apartment. However, it is not only the architectural disposition of dwelling unit and the distribution of a building that mediate different types of subjectivity, but also their mode of operation and their situatedness within the city. Over time, rents in the cooperative development will decrease while rents in the for-profit development will increase; and paradoxically enough, it is the mixed-use offer in the cooperative development that guarantees the attractivity of this otherwise peripheral site. The architecture of Zwicky-Süd, as form, partakes in this partly territorial, managerial and regulatory process—and this partaking expands our definition of architecture as form.

If the stunning shared spaces and experimental floor plans of cooperative housing in Zurich reveal how material form can positively resonate with the lived spaces of its inhabitants, the Zurich case also shows that material form can even give rise to a feedback loop that impacts the regulatory framework. In the 1920s, for example, a push to adopt the garden city as an urban model led to a revision of building laws and would shape Zurich’s first zoning code, adopted in 1946. Nearly one hundred years later, the Federal Office of Housing WBO chose the “cluster” typology created by Duplex Architekten for mehr als wohnen’s House A in Hunziker Areal of 2015, for its design guidelines as exemplary of flexible living forms. However, we argue that architecture can sustain a positive resonance for the practice of dwelling only if society agrees about the purpose and public benefit of the use value of dwelling. If public opinion does not support a commitment to nonspeculation and use value in housing, architectural form alone will have little chance to mediate the social relations of living together and confer a positive resonance with the self, the collective and the city. In this situation, architects, planners and citizens will have to exclusively recur to the first modality of architectural agency and redesign the regulatory framework itself.

3. Insights: Both-And

Our effort to understand how social entrepreneurialism and architectural innovation come together in Zurich in an era of financialized real estate led to three key insights about how cooperatives have bridged seemingly contradictory realms in redefining certain widely held assumptions about the politics of housing.

Affordability Redefined: The Architectural Leverage of Nonspeculation

The first insight distilled from our investigation is that Zurich’s cooperatives have been able to produce experimental architecture precisely because of, not despite their commitment to, nonspeculation and affordability.

Low-rent housing is often conflated with housing of low quality; that is, built with lower-grade materials and featuring standardized apartment layouts. In Zurich’s cooperatives, the opposite is true. Precisely by renting their apartments at below-market rates, cooperatives minimize the risk of vacancy. Precisely because they are not forced to generate returns on investments, they have the leeway to test new forms of living together. For example, conceiving of, realizing and finding residents for the thirteen-room penthouse apartment at Zwicky Süd was possible because Kraftwerk1 was not under pressure to immediately generate revenue for a form of dwelling that the cooperative wanted to launch and test.

Understanding nonspeculation as a condition for design innovation thus challenges the widely held assumption that the best way to achieve low rents is through design. Architectural strategies that have been tested for over a century with this belief in mind include the repetition of standardized elements, prefabrication, and limited floor area. While these strategies can contribute to lowering construction costs and decreasing a building’s carbon footprint, passing on the savings from such architectural decisions to the user happens only if there is a commitment to doing so. Cooperatives, too, reduce apartment sizes and experiment with construction methods, and these strategies do effect rents; in this case, however, rents tend to fall over time because of the cost-rent model, which is tied to investment costs and removes the main contributor to housing prices—rising land values.

Understanding nonspeculation as a condition for high-quality architecture also inverts the neoliberal paradigm which posits that housing built for lower-income groups, assumed to be subsidized, should be of lower architectural quality lest it become desirable for higher-income groups. This neoliberal critique has never quite applied to Zurich’s cooperatives since they are not technically subsidized and have never served only low-income households. At the same time, cooperatives have proven these neoliberal critics right: they have pioneered forms of living together that the private market has copied for higher-income clienteles. For example, “cluster apartments” combining several minimal, single-person dwellings around a large, shared kitchen were first tested by cooperatives but have become mainstream among for-profit residential developers.

The criticism waged at cooperatives most often both from the political left and the political right is that cooperatives are primarily a middle-class proposition and are thus exclusive: residents must have some savings to afford a share in the cooperative, and rents are not pegged to income but result from the cost-rent model and thus often exceed low-income residents’ financial abilities, especially in the case of new construction. Over the life of a property, however, rents tend to decrease, sometimes in absolute terms and always in relation to market rates. Access to cooperative housing thus widens over time.

Zurich’s cooperatives have thus redefined “affordability” by demonstrating that it is a precondition for design exploration while at the same time showing that residents’ incomes are not a precondition for enjoying its advantages. Zurich’s cooperatives illuminate a way out of a bind often faced by potential residents: the choice between “social housing,” where access is restricted by income and availability, and “market-rate housing,” where access is restricted by ever-rising costs. In contrast to both, Zurich’s cooperatives leverage nonspeculation and architecture in equal parts to achieve the goal of at-cost housing open to all.

The Commons Resituated; or, Cooperatives Operate at Once beyond and within the Market

A second key insight to emerge from our study of Zurich’s cooperatives is that these entities, exemplars of the practice of urban commoning, have become actors not only in opposition to but in concert with capitalism.

In the context of today’s low, even negative interest rates, high land values, and de minimis vacancy rates, cooperatives have become more than reliable borrowers; they have become highly coveted. Private banks, institutions and even individual investors today compete with the Zurich Cantonal Bank (ZKB) to sell mortgages. What determines the creditworthiness of a nonprofit entity is the value of its cooperative land. Even if that land technically cannot be sold at market rates, it serves as collateral for various types of long- and short-term loans. This has led to an astonishing situation: the balance sheet of Zurich’s largest cooperative, ABZ, shows 30 million Swiss francs in equity and 1.05 billion Swiss francs in debt. In mid-2020, ABZ was rated by an accredited institution as being on par if not higher-performing and more secure than Switzerland’s largest publicly traded real estate companies. Zurich’s cooperatives thus prove that low-rent housing can be produced and operated in financially lucrative ways, requiring neither extensive state subsidies nor later bailouts.

But the architectural and urban qualities of cooperative developments are precisely where the tension and contradictions between a commitment to nonspeculation and the logic of entrepreneurship become tangible. The current rush by many cooperatives to demolish and replace functional, well-maintained buildings has to do with a lack of buildable land and the political mandate to densify within city limits. Fueling this rush is less residents’ dissatisfaction with their living environments and more the ready availability of capital. Increasingly, such projects have involved centrally located developments noted as historically significant, such as the FGZ’s Friesenberg row houses from the 1920s or ABZ’s Kanzlei perimeter block from the 1930s. In the process, cooperatives often seem to undermine their own goals, since the newly built, larger apartments have higher rents than the ones they replaced, and increased apartment size has led to the actual number of apartments increasing only minimally.

The name of this practice is Ersatzneubau, literally “replacement through new construction.” Cooperatives are under increasing pressure to contribute to the municipal and federal mandates to increase density within built-up areas as part of an effort to combat sprawl and climate change. Arguments made by cooperatives in favor of Ersatzneubau are that the practice is necessary to meet current lifestyle standards relating to the size and configuration of apartments and to comply with new regulations, in particular those related to accessibility and energy efficiency. Redevelopment has been incentivized by revisions to the city’s zoning code allowing for higher density on large, contiguous sites through the tool of the Arealüberbauung, or Planned Development Area. In this way, in areas otherwise zoned for three-story buildings on individual parcels, seven-story structures are permissible on large sites. While citizens and preservationists are increasingly contesting the practice of Ersatzneubau, it has also enabled sensitive, phased renewal intended to keep residents in place, as in BGZ’s work in Schwamendingen.

Cooperatives’ current redevelopment practices, while controversial, bespeak a commitment to and investment in a nonspeculative future. Across their more than one-hundred-year history, not a single cooperative complex has ever “opted out” of its commitment to nonspeculation. In theory, a two-thirds majority of members could, once all public funding has been paid back and pending approval of the municipality, vote to recommodify the housing. But as ABZ CEO Hans Rupp observes, the nonprofit nature is deeply “written into the DNA” of Zurich’s cooperatives. Nevertheless, debates continue. Cooperative leaders are well aware that upgrading neighborhoods or spearheading the development of new ones, as Kraftwerk1 did at Zwicky Süd, can increase the valuation of real estate and lead to gentrification even if the new cooperative apartments are rented at cost.

Autonomy Re-embedded: Private Development Backed by the State

The third key insight from our research is a recognition that the sustained growth of cooperatives across the last century in Zurich was possible only because of their embeddedness with Zurich’s municipal government.

Cooperatives have crafted an image (and self-image) of themselves as autonomous actors creating alternatives to those offered by the market and as doing so independently of the state. Various aspects of their functioning support this image, including self-determination (they select their own members and draft their own bylaws); self-governance (including all aspects of managing, planning and organizing the life of the cooperative); and economic self-sufficiency (as required by cost rent). A sense of being separate and independent has also been a distinct feature of cooperative architecture and urbanism. That is, for much of their history cooperatives have chosen to materialize as distinct entities in the city, both at the scale of the Siedlung and in terms of a uniform architectural expression across individual buildings.

Autonomy is also what has made this model of nonprofit housing politically acceptable from left to right and across shifting political trends, as housing scholar Julie Lawson notes. Geographers Ivo Balmer and Jean-David Gerber explain the continued growth of the model this way: “Housing cooperatives owe their success to the fact that, despite decommodification, they do not lead to an expansion of state control. To a large extent, housing cooperatives are a private, self-organized solution to a public problem.” Nonetheless, even Lawson and Balmer and Gerber go into great detail to explain that continued political and financial support for at-cost housing has been possible only because of the close connections of cooperatives to the workings of municipal governments, as well as initiatives and pressure from organized citizens. Zurich’s cooperatives thus strike an unusual balance: Their claim to autonomy from the state ensures them state support.

Across the last century, this embedded autonomy has led to various forms of state support, the two most significant of which are preferential access to municipal land and preferential access to financing. In 1902, the Canton of Zurich obliged the Zurich Cantonal Bank (ZKB) to lend to cooperatives. In 1910 the required equity was lowered to 10 percent of development costs; in 1924 it was further lowered to 6 percent, where it has remained to this day, enabling cooperatives to obtain mortgages at conventional interest rates but with less than one-third of the equity required of other borrowers. This, in turn, has allowed cooperatives and policymakers to argue that cooperatives are self-sufficient entities that, despite enjoying preferential access to land and financing, should not be considered subsidized. Not technically being subsidized means, in turn, that residents are not subject to income restrictions, which in turn reinforces the sense of cooperatives as autonomous, self-governed communities. All in all, the preferential access to financing has led to an outstandingly diverse field of 141 cooperative organizations in Zurich that today collectively manage over 42 000 apartments—a remarkable realization of collective self-determination and social entrepreneurship that reconciles the strive for individual singularization with the collective.

This embedded autonomy is the result of a continual push and pull between activists and citizens on the one hand and city officials on the other. The Kalkbreite cooperative, a mixed-use development realized on centrally located, municipal land, is a primary example of the effectiveness of a citizen-led campaign to convince the City of Zurich to rededicate a municipal site formerly considered unsuitable for residential use and grant it to a cooperative through a leasehold. The open architectural competition for this project, however, was the result of a municipal policy crafted within city government. In the early 1990s, the city prioritized new residential construction for families and coupled this with requirements for higher-quality designs and transparent selection processes.

Together, these three key insights challenge some of the most persistent assumptions held by architects, planners, scholars, the general public and policymakers about housing—assumptions often framed as mutually exclusive dichotomies rather than as examples of “both-and.” The affordability of housing is the result of nonspeculation and can never be achieved by design alone. The interplay of a nonprofit mission in housing and a profit-driven financial market is real. And even independent, private actors depend on the regulatory powers of the state to flourish. Together, these three insights help to explain what makes social entrepreneurship and architectural experimentation possible in Zurich even during an age when striving for singularities may be limiting our idea of the good life.

4. Acknowledgements: A Cooperative Project

Cooperative Conditions was developed with seventeen students in the Master of Advanced Studies Program in the History and Theory of Architecture (MAS gta) at ETH Zurich in the spring of 2020. A joint research project is an integral part of the curriculum of this part-time, post-professional, two-year course; students contribute to a given topic with the goal of producing a publication, exhibition or other public format.

When we began, we had already defined the eight conditions we would explore. We had also determined that students would conduct interviews, engage in archival research and synthesize the findings using an analytical framework organized around Instruments, Historic Origin and Agency. The interviews were most revealing with respect to the relationship of architecture, finance and regulation. We spoke not just with architects and city officials, typically eager to share their views on design and policy, but with the chief executives of cooperative organizations, pension fund managers and bankers. The latter conversations provided insight into the financial dimensions of architectural decisions that even these decision-makers themselves had rarely considered.

The direction and outcome of the research, however, evolved through a continual back and forth among students and instructors. This included the choice of Instruments and the selection of projects to best highlight Agency. Students often took the initiative. They expanded the range of projects to consider and people to interview, and Rebekka Hirschberg proposed film as the best medium to capture the projects’ atmospheres.

In translating the research into graphic form, the feedback and art directorship of Berlin-based graphic studio Monobloque were critical. First Dorothée Billard, then also Clara Neumann, gave shape to aspects of cooperatives that are often discussed but rarely made tangible. Key visualizations include how cost rent develops over time and the relation of equity to various forms of debt.

For the exhibition and this web page, we developed a combined framework to bring together short texts, original graphics and contemporary and historical images. The inextricability of courtyard configurations, interest rates and municipal rulings becomes apparent through the juxtaposition of different artifacts. Visitors will thus find, side by side, a Twitter feed charting the results of a 2020 referendum on housing, an album page commemorating the 1931 World Cooperative Day and contemporary photographs (taken by students) of cooperative spaces.

The website captures a work in progress, at a half-way point between exhibition and book.

Cooperative Conditions, then, is a product of minds working in cooperation to create a primer on architecture, finance and regulation. It was made possible by the many individuals and organizations who contributed knowledge, time, humor and, not least, money. They did so out of a sense that the potential and possibilities of this project would be worth the effort. Thank you.

1.

An Idea of Sharing

Sharing is the foundation of any cooperative enterprise. Sharing occurs in three overlapping realms: labor and resources; property; governance. Sharing means access to more not less—not only for the cooperative community but for society at large.

Photo: Anna Derriks

Agency

Shared governance plays out directly in planning decisions. In a cooperative, members elect the board; approve expenditures, investments and future expansion; and are encouraged to serve on committees that discuss everything from community building to entrepreneurial strategy. This creates an ongoing feedback loop allowing management to respond to members’ changing needs.

Shared governance and shared ownership directly shape the configuration of cooperative architecture. This might result in large, landscaped courtyards rather than small private patios; hallways used not only to access dwelling units but for interaction; and laundry rooms designed to accommodate washing machines and to encourage children’s play. Because residents are at once co-owners, co-governors and co-users, they trust one another in the use of these shared spaces.

The conviction that resources are limited and must be shared has encouraged cooperatives to respond with new spatial strategies. These include lowering the size of dwelling units while increasing amenities that are available to all; locating intermittently used spaces such as guest rooms outside of the apartment; and offering a range of apartment configurations to accommodate changing household needs.

Instruments

Shared Labor and Resources

A cooperative is a community whose members advance common interests by sharing labor and resources. Any surplus value is shared equally among members. This practice is referred to as “mutual self-help” and is often possible only through uncompensated, volunteer labor.

Shared Property

A cooperative is a corporation co-owned by its members. Members become co-owners of a housing complex when they become residents and buy a share.

Shared Governance

A cooperative is a legal entity co-governed by its members. Its bylaws define the rules of governance. These generally adhere to the democratic principle of one member, one vote. The commitment to nonspeculation is an integral part of any Zurich cooperative’s bylaws.

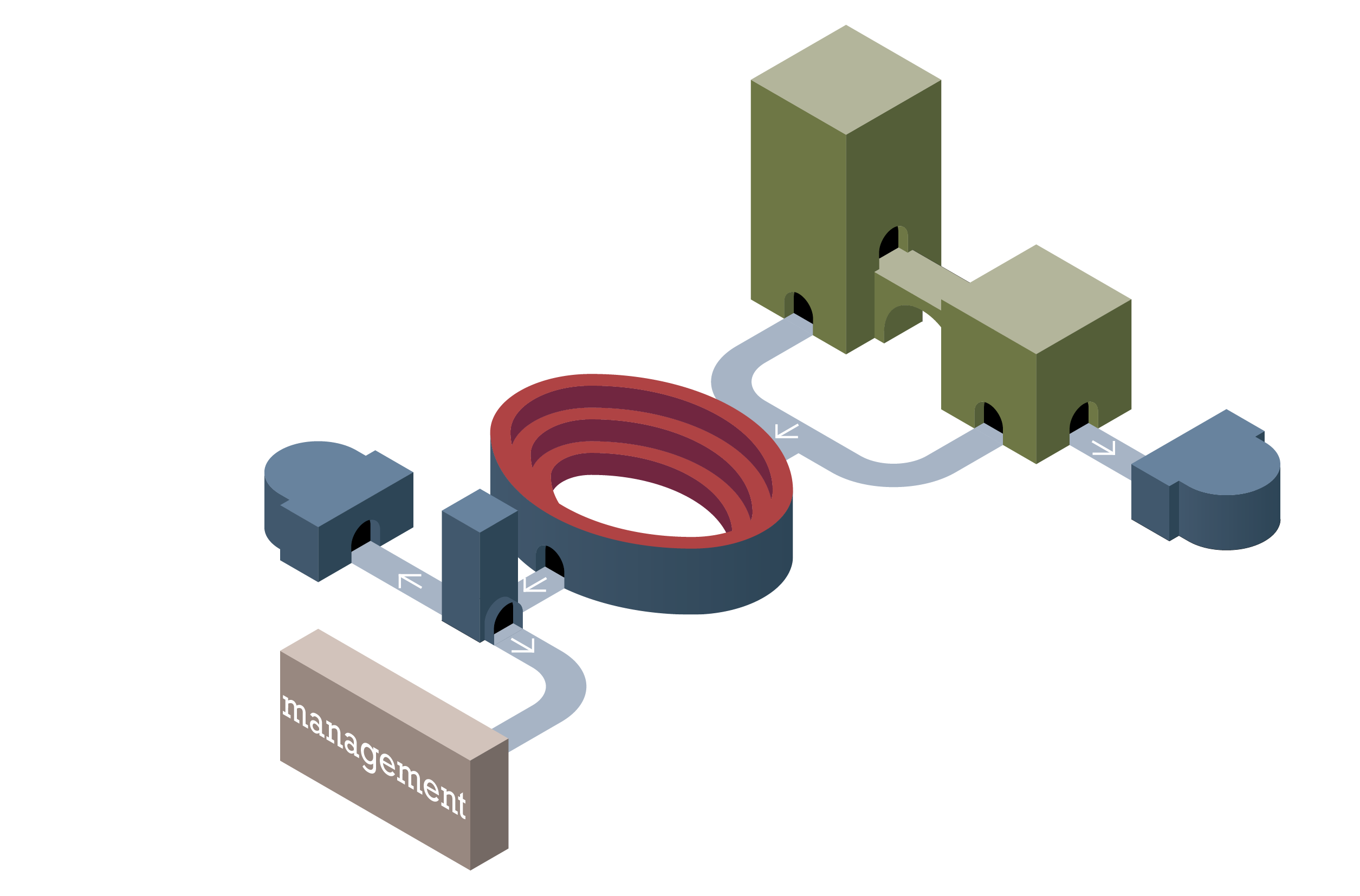

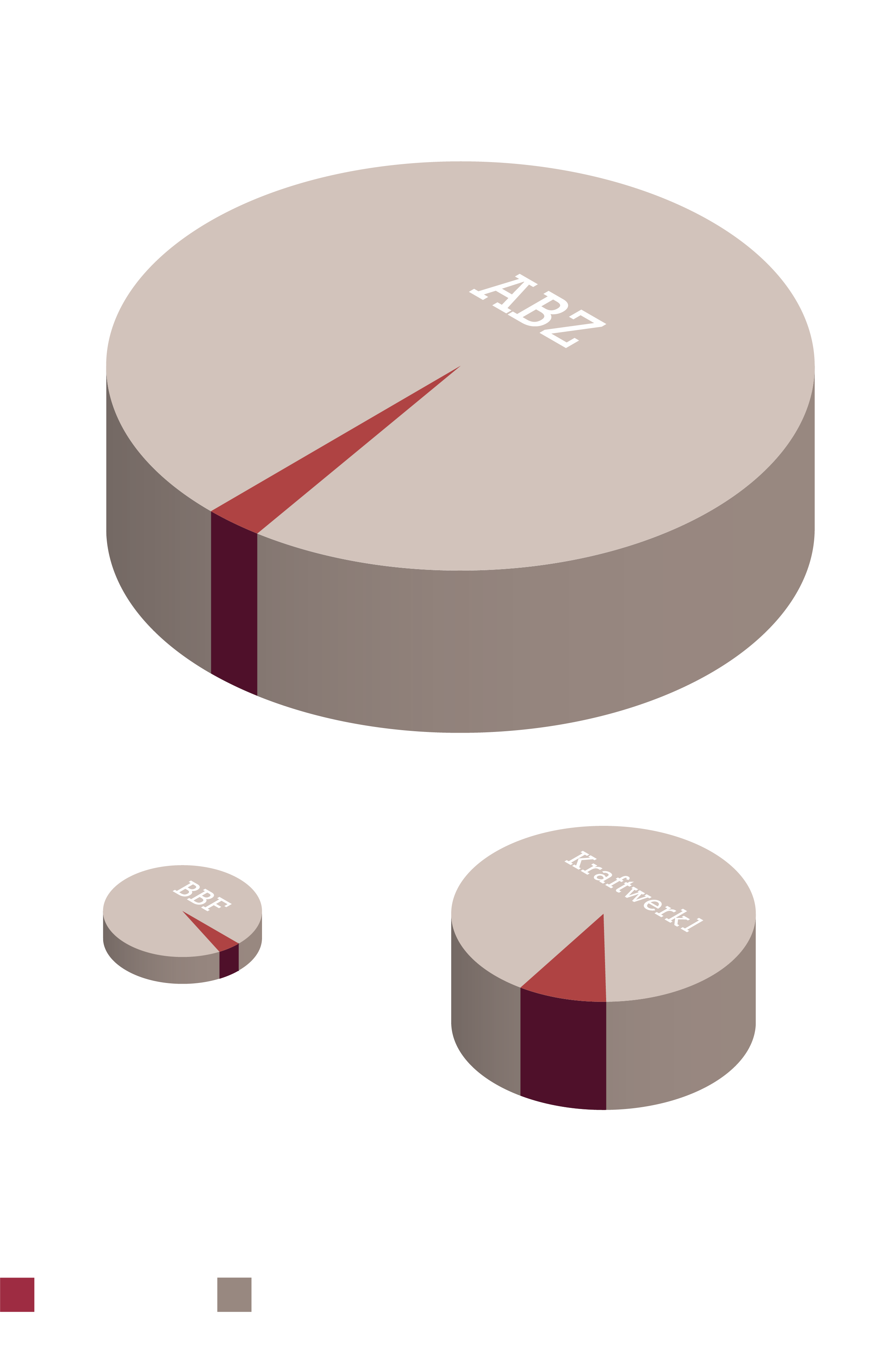

Visualization: Monobloque

Source: Cooperative organizations (ABZ, Kraftwerk1 and Kalkbreite)

Zurich cooperatives can vary in structure depending on size and mission, but some features are common to all. Members elect the (volunteer) board and various (volunteer) committees, and the board makes strategic decisions and appoints the (professional) management. The purchase of a share makes a member a resident and co-owner of the cooperative.

Documents

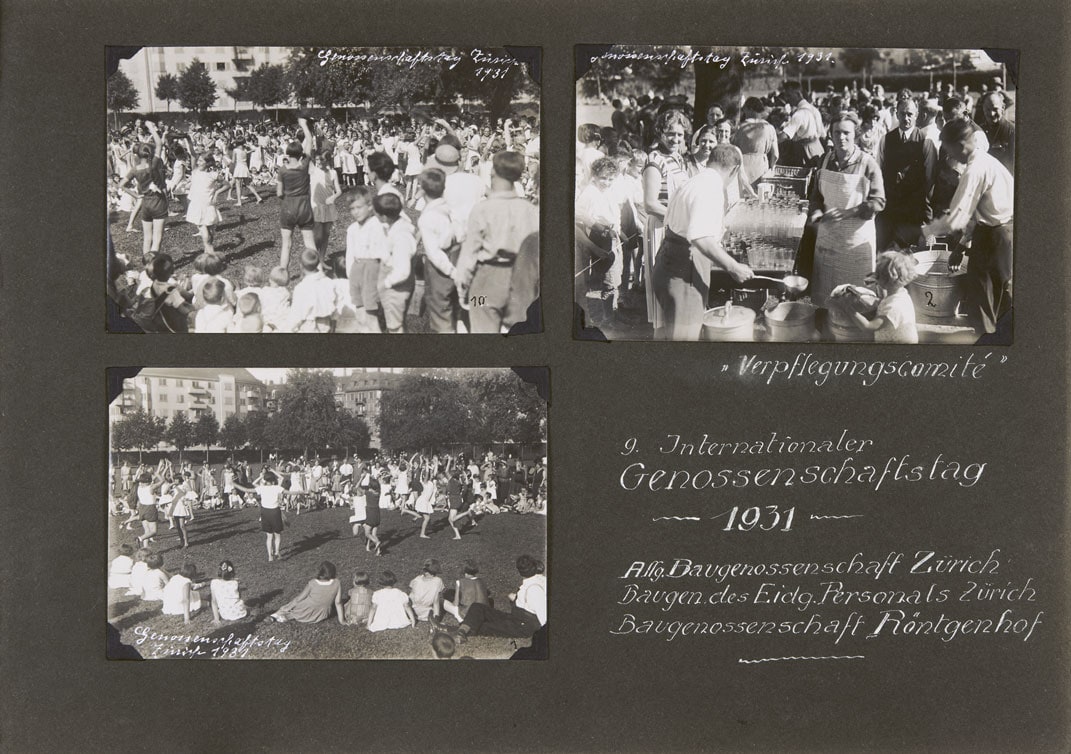

Source: Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv (ABZ F.03.2.30)

This event, staged to draw in the wider public, sought to spread the main idea animating cooperatives: collective action for shared benefit rather than competition for individual gain. That idea, itself older than capitalism, was transposed to housing production in industrializing Europe during the mid-nineteenth century. It was a response to the inability of both the state and private enterprise to respond to the housing and other needs of the working class and small entrepreneurs.

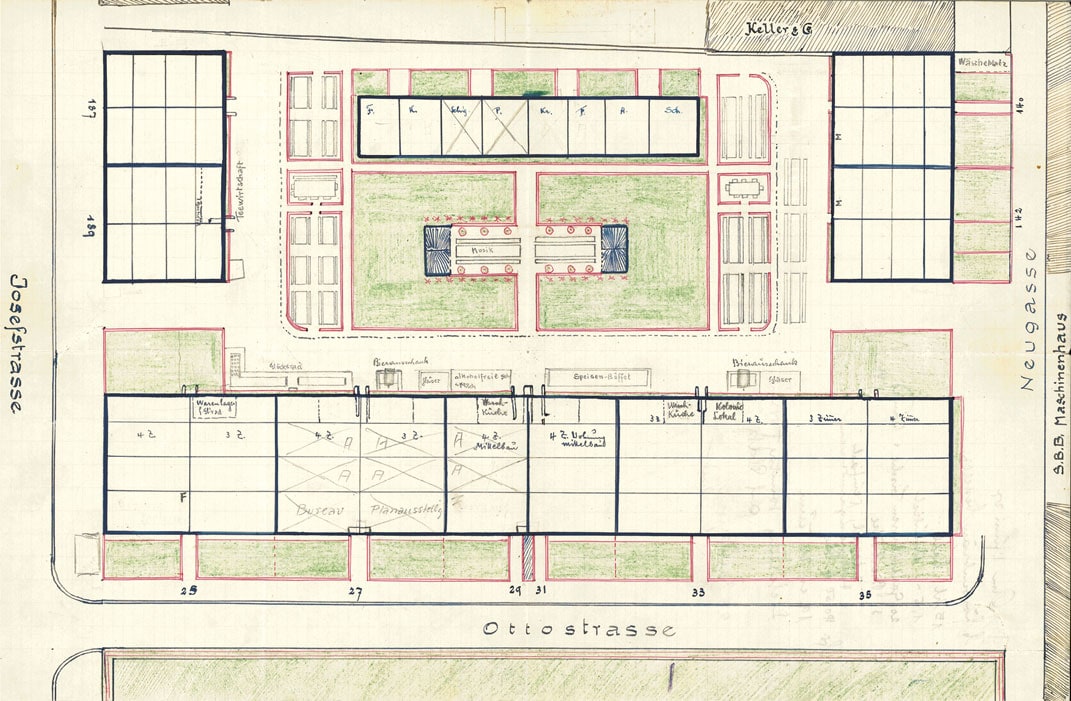

Source: Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv (ABZ A.32.15)

The markups in colored pencil show the temporary installations made for the festivities on the occasion of the complex’s opening in 1927. The drawing reveals the close attention paid to collective activities in shared spaces: a music stage in the center of the courtyard, seating and buffets, and even a lucky wheel. In one ground-floor apartment the cooperative exhibited architectural plans for the complex. It also furnished two apartments as showrooms for interested visitors.

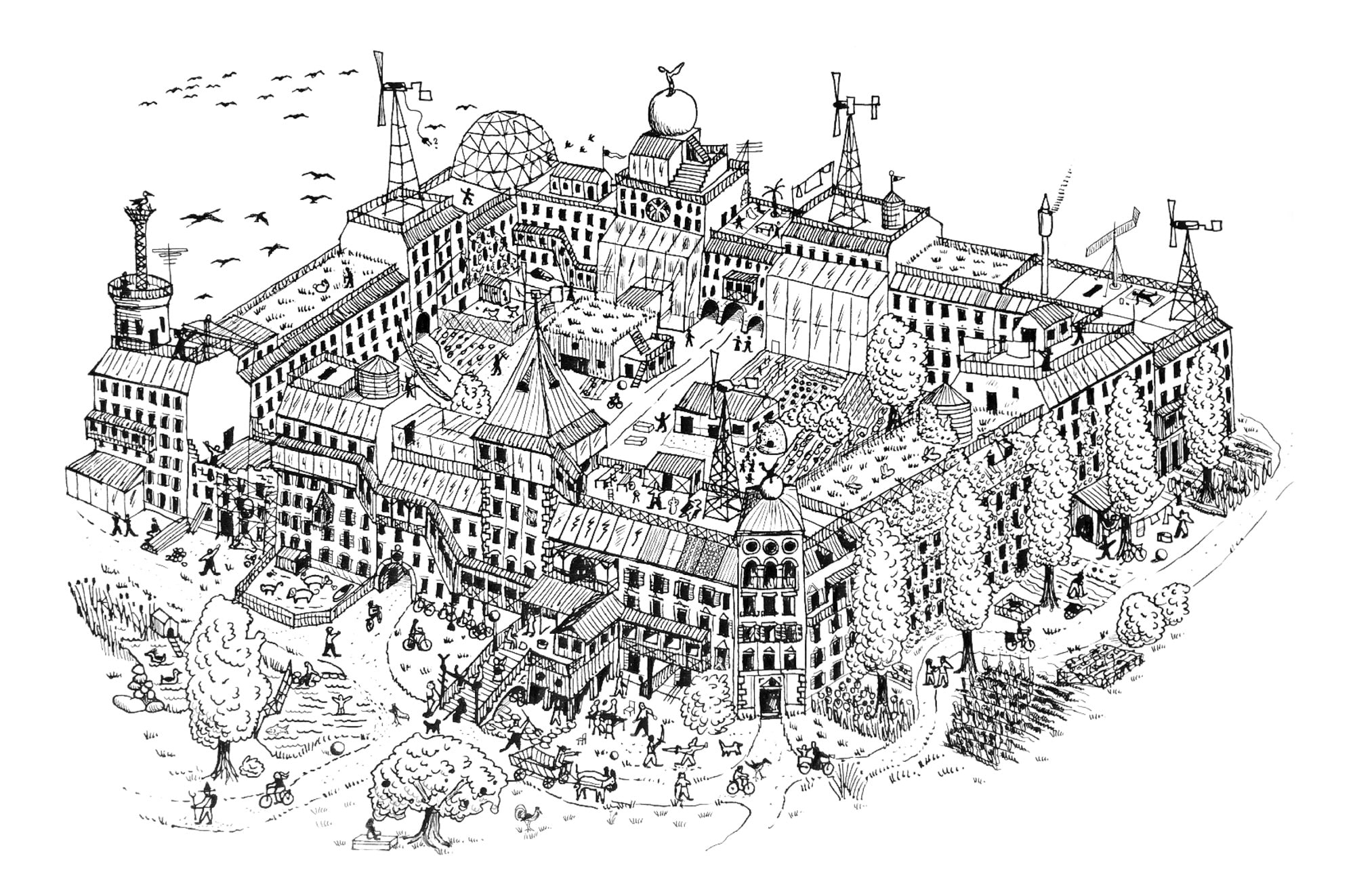

Source: P.M., bolo'bolo, Paranoia City Verlag, Zurich 2015 (1983)

Writing during the youth protests, a period when squatting was common in Zurich’s inner-city, the activist Hans Widmer proposed a self-sufficient alternative to capitalist housing production: the “bolo.” Capable of accommodating several hundred people, “bolos don’t have to be built in empty spaces. They’re much more a utilization of existing structures. In larger cities, a bolo can consist of one or two blocks, of a smaller neighborhood, of a complex of adjacent buildings. You just have to build connecting arcades, overpasses, using first floors as communal spaces, making openings in certain walls, etc. So, a typical older neighborhood could be transformed into a bolo like this.”

Photo: Gerda Tobler/Kraftwerk1

The Sofa Uni was a one-month installation in an industrial building conceived as a laboratory for new forms of large households. The event was initiated by a group of squatters, activists and architects dissatisfied with the type and cost of new housing in Zurich. It led to the creation of a new cooperative organization, Kraftwerk1. In their first publication, Kraftwerk1’s founders wrote, “What may be lacking in terms of individual comfort will be provided—just as in a high-end hotel—through shared luxury.” Other new cooperatives were founded in the 2000s following Kraftwerk1’s example.

Research: Kadir Asani, Armin Fuchs, Abbas Mansouri

2.

Public Opinion

To grow beyond individual initiatives, cooperatives need political support, which is dependent on public opinion. In Zurich, pro-cooperative policies won important political victories in the 1920s, 1940s and late 1990s, resulting in a significant increase in cooperative housing.

Agency

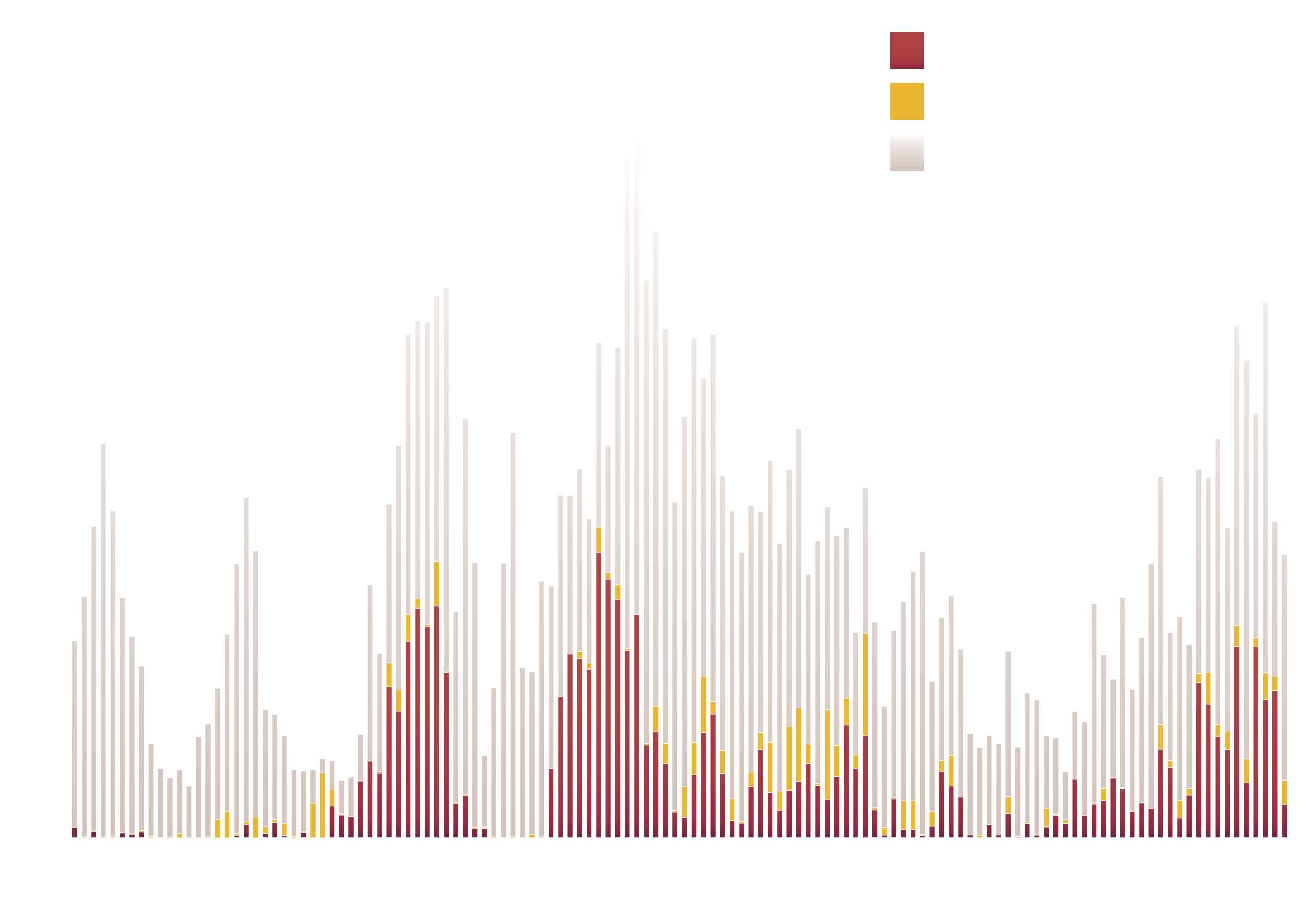

In Zurich, surveys have been instrumental in shaping public opinion and public policy on housing since the late nineteenth century. Housing policy has been continually debated, contested and revised by citizens and elected officials in part through referenda. Swiss voters are called to the polls every three months; ballot measures on land-use policy and housing appear every few years.

Public opinion, public policy and architecture are mediated through design guidelines and housing regulations issued by public-sector entities. Zurich’s cooperatives, because they are nonprofit, must adhere to both federal design guidelines and cantonal housing regulations. As such, they, too, are a product of societal consensus.

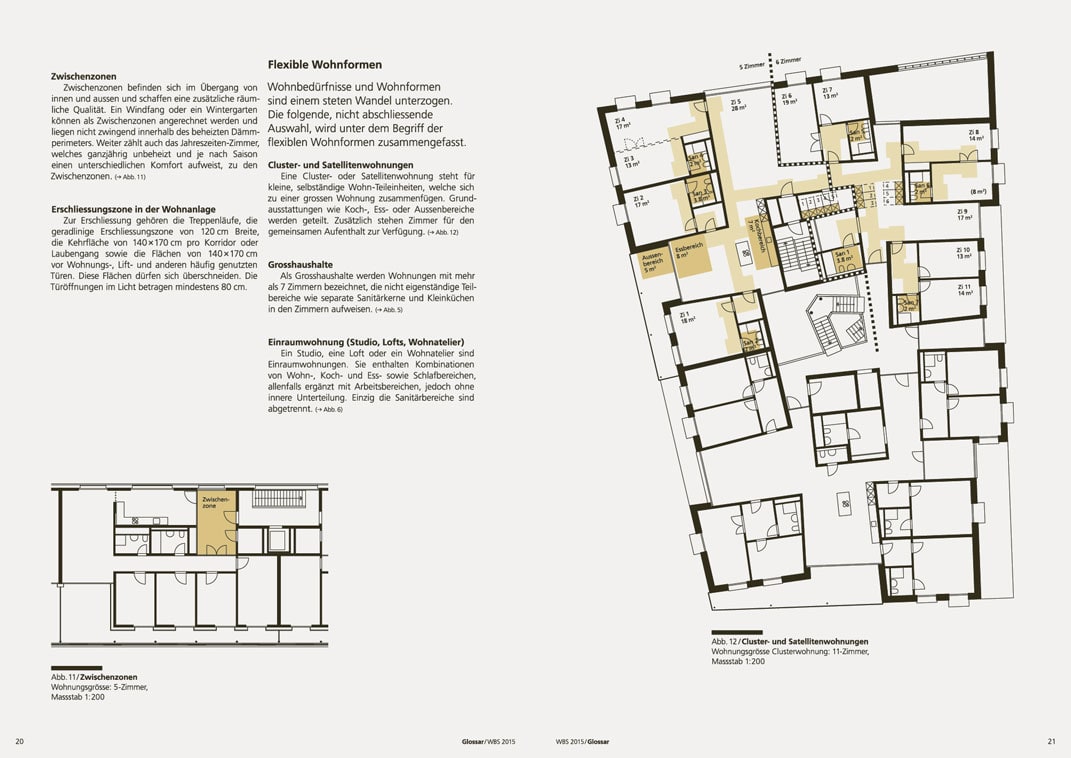

However, public opinion can be swayed by the tangibility of architecture. A striking example is the highly experimental cluster floor plan designed by Duplex Architekten für Hunziker Areal in Zurich, which was included in federal design guidelines (the Wohnungs-Bewertungs-System) only a few years after the project’s realization. Its inclusion signified an epochal shift: a move beyond the nuclear family as the normative household model.

Plan courtesy of Duplex Architekten

Instruments

Referendum

A referendum (Volksabstimmung) asks voters to approve or reject a particular ballot measure; if approved, the measure becomes law. In Switzerland, a mandatory (obligatorisches) referendum is required for any constitutional change, while an optional (fakultatives) referendum can be initiated by citizens in opposition to any law passed by the Swiss legislature (so long as 50 000 signatures asking for the referendum are collected within 100 days of the law’s publication).

Popular Initiative

A referendum can also result from a popular initiative (Volksinitiative) on any matter of common concern. To force a vote at the national level, a petition requires 100 000 signatures.

Survey

A survey, study or report is an inquiry into the causes of social problems. It is generally written by experts commissioned by a public entity or philanthropic organization. Its normative power derives from the presumable objectivity of science and allows policy makers to argue for or against public-sector involvement in housing.

Visualization: Monobloque

Source: Statistik Stadt Zürich

Documents

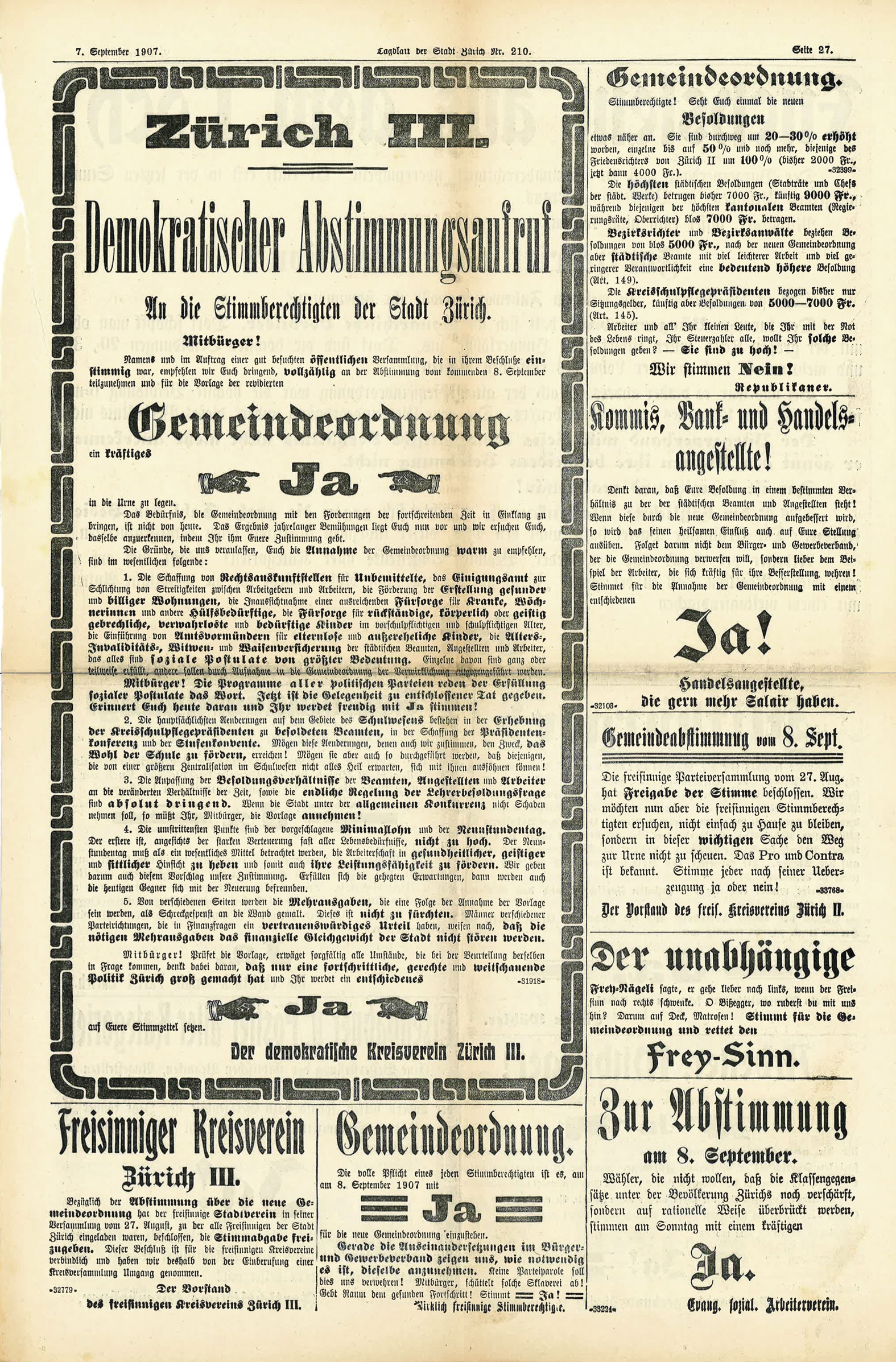

Source: Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv (Ar 32.90.5)

In 1896, a civic organization commissioned the first inquiry on the sanitary conditions of industrial workers’ housing. The study paved the way for the City of Zurich to define housing as a public-sector responsibility in its 1907 charter revision. An advertisement in the Tagblatt der Stadt Zürich called for voters in the city to approve the revision in a mandatory referendum. The revised charter was the first to define housing as a matter of public concern and as worthy of public-sector support.

Photo: Wilhelm Gallas/Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

Even though it was a nonbelligerent, Switzerland experienced hunger, rampant inflation, a flu epidemic and a severe lack of housing in the aftermath of World War One. By official count, in 1919 only 20 apartments in Zurich were vacant out of a total of 47 000. These conditions contributed to a nationwide general strike. The emergency measures approved in response—federal subsidies for nonprofit housing in 1918 (loans and grants), the establishment of the Swiss Housing Federation in 1919 and the 1924 municipal ruling to lower cooperatives’ equity requirements from 10 percent to 6 percent—had lasting impacts at the municipal and national levels.

Source: Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv (F Pe-0910)

Photo: BWO, Wohnbauten planen, beurteilen und vergleichen. Wohnungs-Bewertungs-System. Grenchen, 2015

The 2015 Wohnungs-Bewertungs-System (Housing Evaluation System, WBS) chose the “cluster” typology designed by Duplex Architekten for Hunziker Areal in Zurich as exemplary of flexible living forms. The plan organizes five one- and two-room-apartments, each with an individual bath and kitchenette, around generous shared spaces.

Source: twitter.com/Wohninitiative

The initiative asked voters whether all municipalities in Switzerland should be required to guarantee a certain percentage of nonprofit housing. Slogans for the initiative included, “Stop Speculators,” and slogans against included, “No to the Nationalization of the Housing Market.” The initiative was rejected by 57 percent of voters.

Research: Gina Rauschtenberger, Alexia Zeller

3.

Nonspeculation

Nonstandard, experimental forms of living together are possible in Zurich precisely because cooperatives reject the notion of exchange value in architecture. The resulting high use value benefits not just current residents but future generations.

Photo: Kristin Sasama

Agency

Nonspeculation has immediate implications for design. This is especially true within a heated real estate market with virtually no risk of vacancies, such as Zurich. Whereas for-profit developers tend to see a hot market as a reason to follow existing practices, Zurich’s cooperatives see an opportunity to test new forms of living together.

The key instrument for nonspeculation is cost-rent, which works best over time. Upon completion of a new construction project, cost rent is only slightly below market rent. Over time, however, cost rent declines relative to market rates because loans are paid off and rising land values are not reflected in its calculation. Today, rents of cooperative apartments in Zurich are, on average, 25 percent below market rents.

Taken together, the commitment to nonspeculation and cost rent encourages careful and continuous stewardship of architectural and social structures. Even in highly coveted central locations, cooperative organizations can renovate complexes in response to changing standards or regulations but still keep rents low enough to maintain social and economic diversity.

Instruments

Gemeinnützigkeit

Gemeinnützigkeit is a legal term for a nonprofit enterprise with public benefit. For cooperative housing, it means a permanent commitment to the provision of housing under the premise of nonspeculation. Land and buildings are removed from the private market and apartments priced following the cost-rent model.

Cost Rent

Cost rent is a mode of rent calculation that neither requires subsidies nor generates a profit. It is determined by a formula which incorporates investment value and building insurance value, multiplied by benchmark factors that are regularly adjusted by municipal and federal agencies in relation to interest rates and maintenance costs.

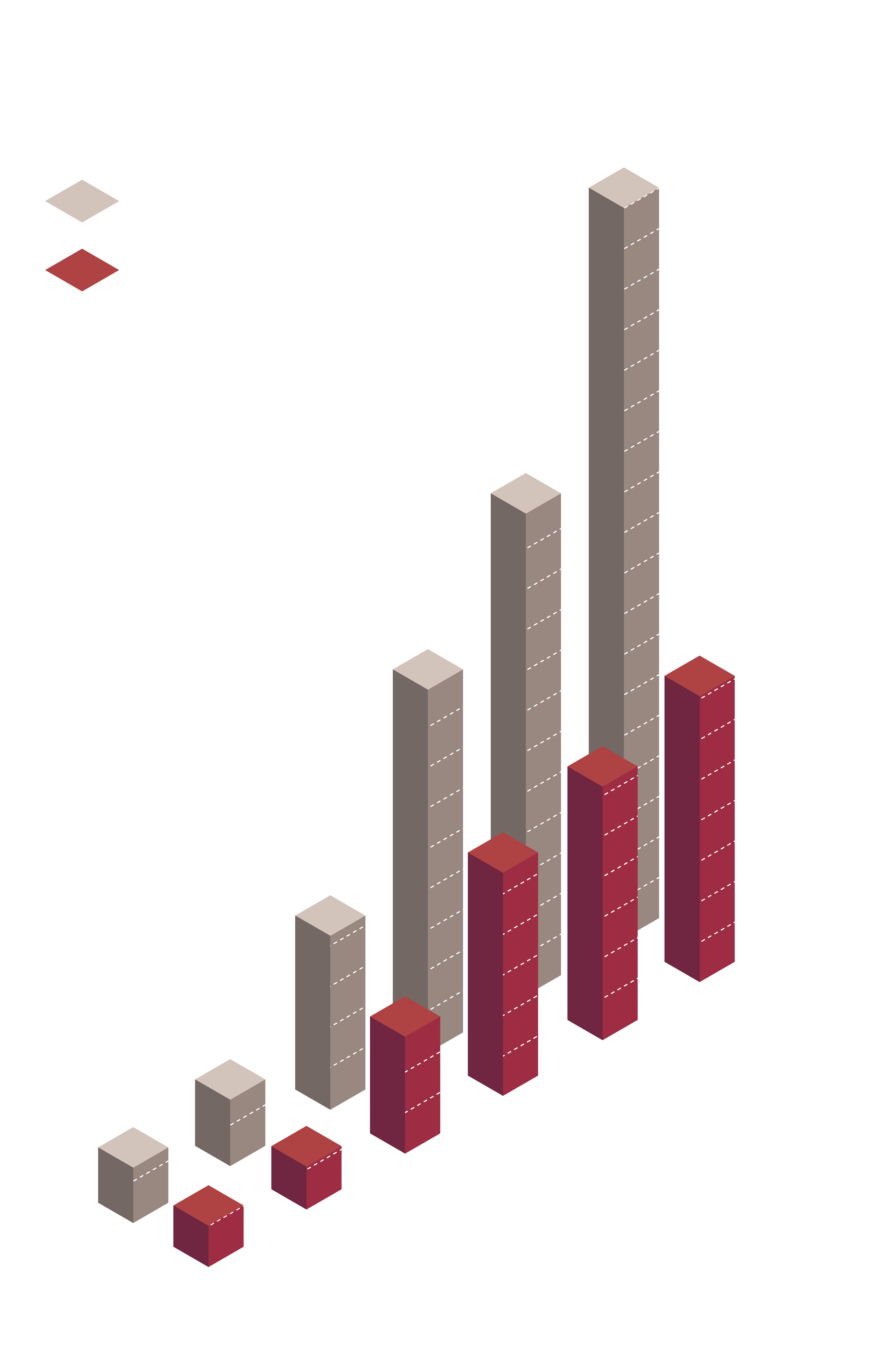

Visualization: Rebekka Hirschberg & Monobloque

Source: ABZ (Annual Reports 1927–2019) and Statistik Stadt Zürich

Visualization: Rebekka Hirschberg & Monobloque

Source: ABZ (Annual Report 2019)

The maximum cost rent for a property is calculated using a formula based on the property’s building insurance value and investment value. These values are multiplied by factors based on the benchmark interest rate and operating quota, a coefficient defined by the City of Zurich that represents the estimated operating costs. The sum equals the property’s maximum allowable rental revenue. These values change over time, as the example of ABZ’s Siedlung Ottostrasse shows. While cost rent increases over time, it does so more gradually than market rents because the land value of a cooperative does not increase and cooperatives are not allowed to generate profit.

Documents

Source: Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

Source: ABZ Archives

Ottostrasse, completed in 1927, demonstrates how a cooperative complex, even in a central location, can retain its original architectural features while being continually upgraded and maintaining low rents. The three-room apartments today rent for around 650 Swiss francs a month (and an initial share purchase of 3 000 Swiss francs), which is more than 50 percent below the market rent for comparable apartments in the area.

Photo: Gertrud Vogler/Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv (F 5107-Na-11-006-006)

In the 1980s, Zurich youth protested the municipality’s development policies with a range of actions, including squatting and happenings. The youth opposed policies that favored the demolition of existing housing to make space for new construction of office and commercial space.

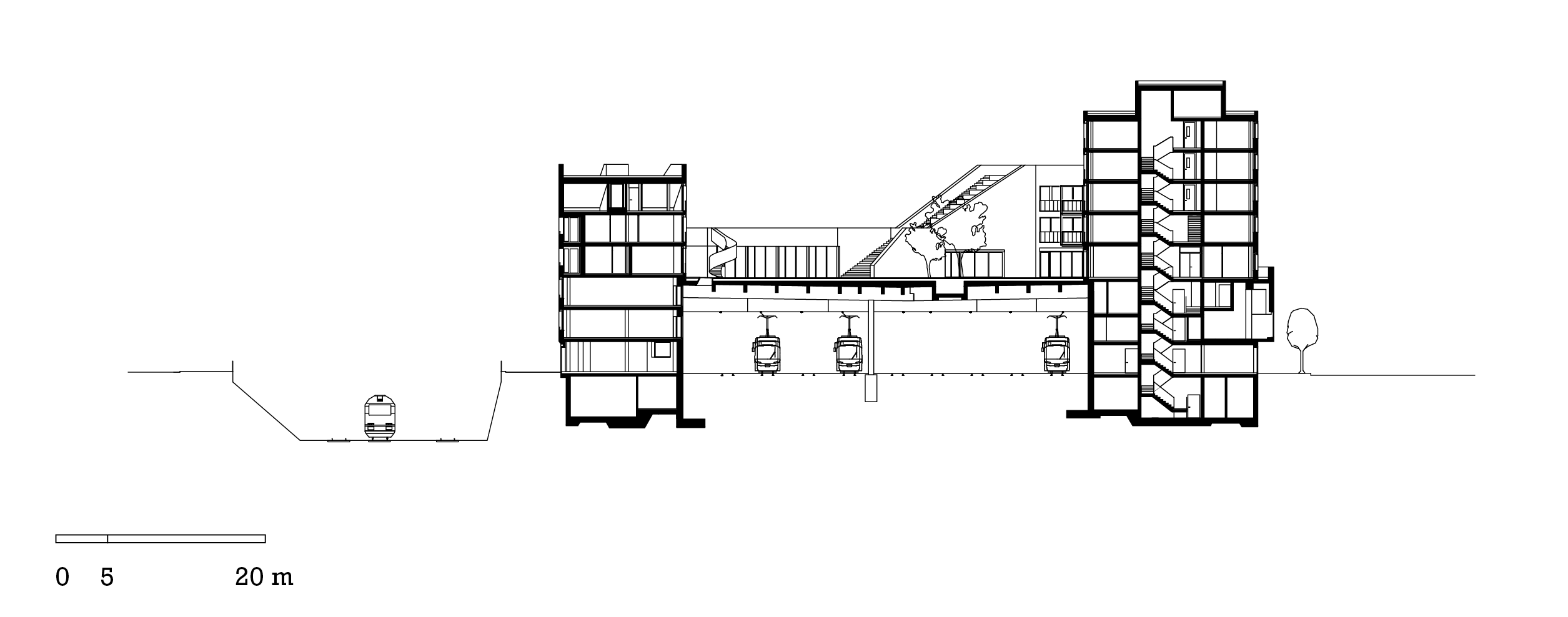

Zwicky Süd, completed in 2015, is a former industrial site just beyond Zurich’s city limits that was codeveloped 50/50 by Kraftwerk1 (a cooperative) and two for-profit pension funds with a single architectural firm, Schneider Studer Primas.

Plan courtesy of Schneider Studer Primas Architekten

Plan courtesy of Schneider Studer Primas Architekten

The floor plans for three-room apartments reveal the design priorities of nonprofit and for-profit developers. The apartments designed and realized for Kraftwerk1 are accessed by a shared exterior gallery, reflecting the emphasis on casual social contacts, and exhibit interior flexibility. The pension funds requested and realized a more standard layout: access is through a core, and rooms have doors and defined uses.

At the time of completion, cooperative and market rents differed by approximately 20 percent. Over time, they will diverge more dramatically because maximization of revenue drives the pension funds, while decision-making in the cooperative is focused on keeping rents low in line with the cost-rent model.

Research: Lale Geyer, Rebekka Hirschberg

4.

Equity

The limited amount of equity required for cooperatives to take out a mortgage gives even socially marginalized groups access to financing. This has led to a great diversity of many small, specialized organizations that offer specific forms of living together to very different interest groups.

Agency

A cooperative’s equity is crowdsourced from individuals whose desires and needs are known to the organization’s management. This allows the cooperative to develop housing models specific to its members’ needs. The Siedlung Lettenhof, for example, was developed in the 1920s by and for single, women professionals whose only housing options at the time were subletting or living with relatives.

Source: gta Archives/ETH Zurich, Lux Guyer

In cooperative housing, the return on an individual’s equity investment is paid out in use value, not cash. This “use value dividend” includes a life-long right to stay, cost rent and collective self-governance.

A cooperative’s limited equity has outsize financial leverage not only in the short term but over time. While a cooperative’s land and buildings cannot be sold at market rates, they can be used to take on more debt for new development projects, resulting in an even lower equity-to-debt ratio than has been required since a 1924 municipal resolution. The larger and older a cooperative, the greater the leverage of its equity.

The preferential access to financing has led to an outstandingly diverse field of 141 small and large, young and old cooperative organizations in Zurich that today collectively manage over 42.000 apartments embodying various forms of living together.

Instruments

Municipal Resolution

Zurich’s housing cooperatives need only 6 percent equity to access a conventional bank loan, far less than the 20 percent typically required. This has been the case since a 1924 municipal resolution in which Social Democrats and conservatives struck a compromise to support cooperatives in the face of a dire housing shortage.

Share

A cooperative’s equity is crowdsourced among its residents through the sale of shares. A share is a certificate of partial ownership of the cooperative corporation and entitles residents to participate in the governance of the organization.

Savings Bank and Solidarity Fund

Zurich cooperatives generate additional financing through two self-managed instruments. A cooperative’s savings bank allows members to deposit money and earn a low interest rate in return. A cooperative’s solidarity fund pools contributions to aid residents in case of financial need.

Visualization: Monobloque

Source: Annual reports of the three cooperatives from 2018

The three cooperative organizations ABZ, BBF (cooperative for working women), and Kraftwerk1 differ in age, size, philosophy and equity as a share of their overall balance sheet. A cooperative’s willingness to take on more debt is shaped by whether it owns or leases the land on which it has built.

Documents

Source: Stadtarchiv Zürich

Share prices vary depending on the age and location of the complex, as well as the size and location of the apartment. Today, the cost of a share for a three-room apartment in a Zurich cooperative ranges from 8 000 to 50 000 Swiss francs.

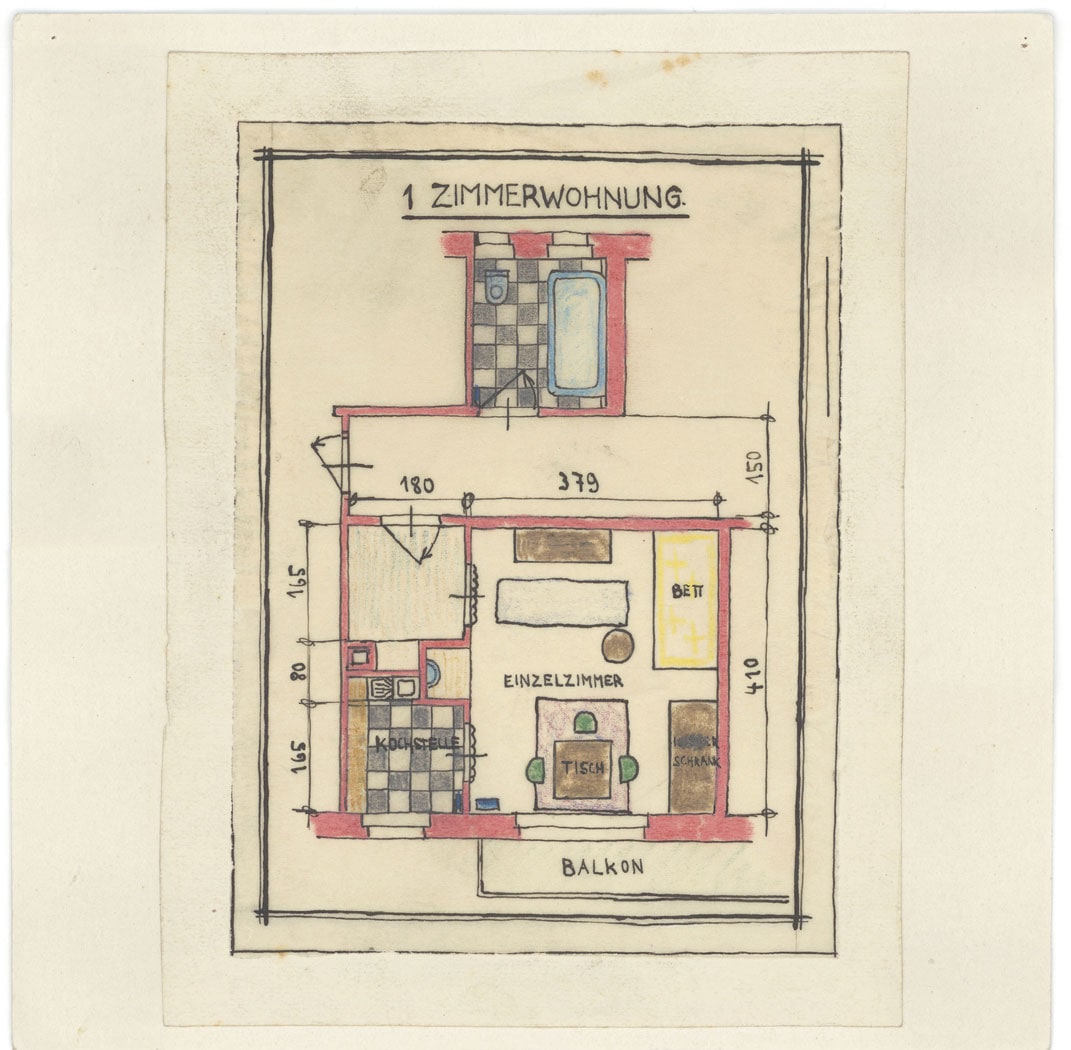

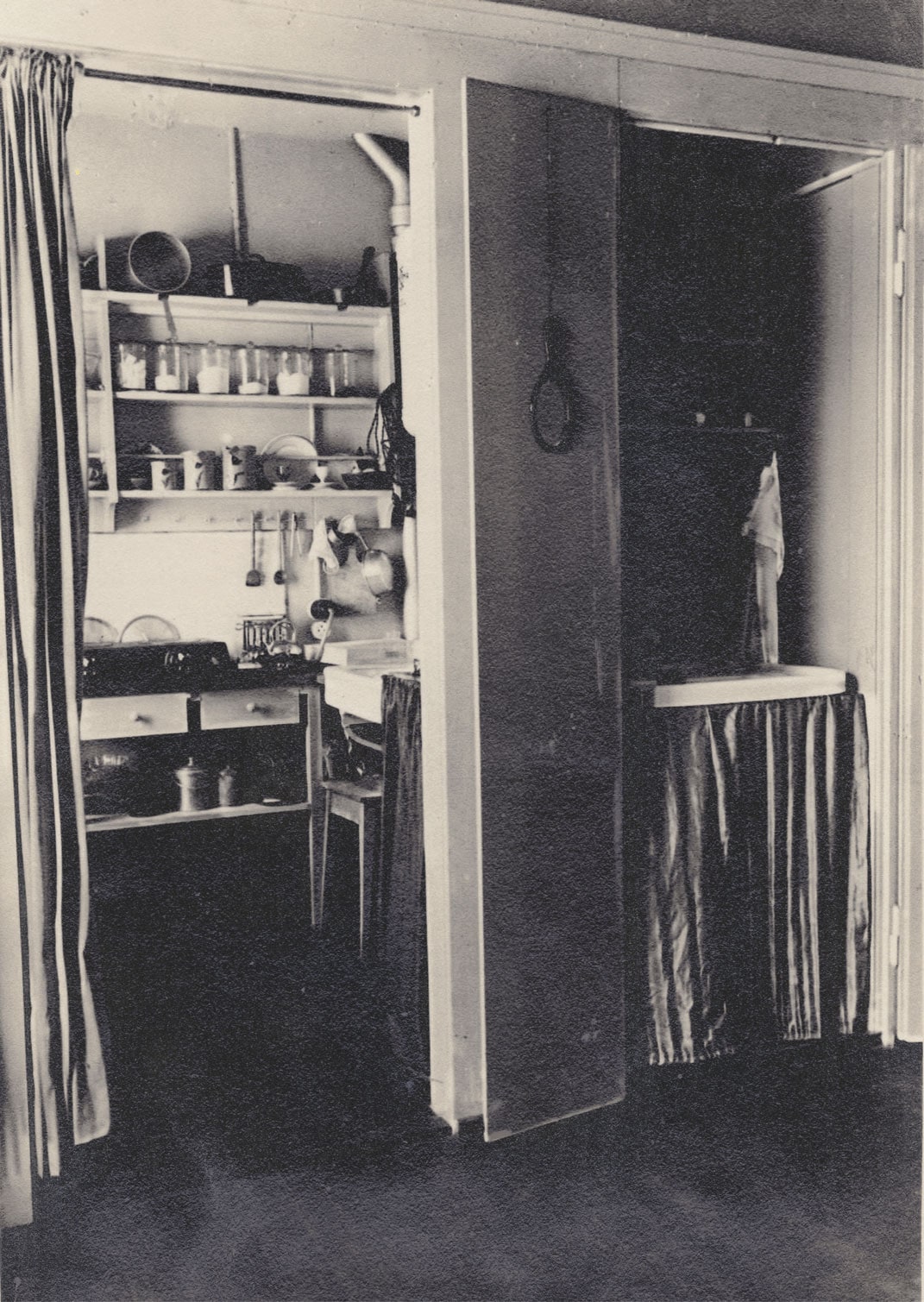

Source: gta Archives/ETH Zurich, Lux Guyer

Lettenhof provided a range of apartment sizes to accommodate a range of resident needs and financial capabilities. The majority of the apartments at Lettenhof were designed to provide maximum privacy to their residents. A private kitchen and bath, as well as one or two private balconies, were important elements in this strategy. The studio was the only apartment type to have a shared bath and only a small kitchenette.

Source: Archives of Baugenossenschaft berufstätiger Frauen

Source: Archives of Baugenossenschaft berufstätiger Frauen

In an article titled “Single working women created a homestead for themselves,” the author focuses on the unusual liberties afforded to the doctors, teachers and administrators living in Lettenhof.

Research: Hanae Balissat, Kristin Sasama

5.

Debt

Around 80 percent of the value of Zurich’s cooperatives is debt. Private and public-sector lenders alike consider cooperatives to be reliable borrowers and to provide lucrative investment opportunities, a status materialized through architecture that is built to last.

Photo: Anna Derriks

Agency

For Zurich cooperatives and their lenders, debt means security. Debt is not seen as a short-term, high-risk endeavor but rather is understood as a long-term commitment. As a result, architecture is built to last for generations. This plays out in the choice of high-quality building materials, whether in façades, floors or hardware. Siedlung Friesenberg, for example, has been in use for close to a century.

For lenders, cooperatives provide lucrative investment opportunities. Zurich’s minimal vacancy rate of 0.15 percent ensures that cooperative apartments, offering high use value at low cost, will never go unrented. For cooperatives, a choice of lenders allows debt to be rescheduled at favorable rates. In turn, this gives cooperatives the leeway to pursue nonstandard architectural solutions.

For cooperatives, servicing long-term debt goes hand in hand with a willingness to take risks on endeavors that may only play out in the long term. This includes developing large-scale projects in the urban periphery and embracing urban design to encourage the use of open space by diverse actors, such as the Glattpark development near Zurich Airport.

Instruments

Loans from Conventional Banks

Most of the debt owed by Zurich cooperatives was obtained from banks at conventional interest rates. These first mortgages typically cover 60–80 percent of development costs. The Zurich Cantonal Bank (ZKB), a private bank backed by the Canton of Zurich, has had a legal obligation to lend to cooperatives since 1902. (

Loans from Pension Funds and Other Private Entities

Since 1992, most cooperatives have also obtained second mortgages, which fund 14–34 percent of development costs, from the City of Zurich Pension Fund. This is a private institution whose lending to cooperatives, however, is backed by the City of Zurich. Additional long- and short-term loans are made by a variety of private individuals and institutions. (

Loans from the Public Sector

The public sector, whether at the municipal, cantonal or federal level, provides few direct loans to cooperatives. The indirect mechanisms for low-interest loans include the Swiss Bond Issuance Cooperative (Emissionszentrale), which since 1990 has enabled cooperatives to refinance loans upon completion of a project. A revolving fund (fonds de roulement) has been lending up to 50 000 Swiss francs per dwelling unit since 2007.

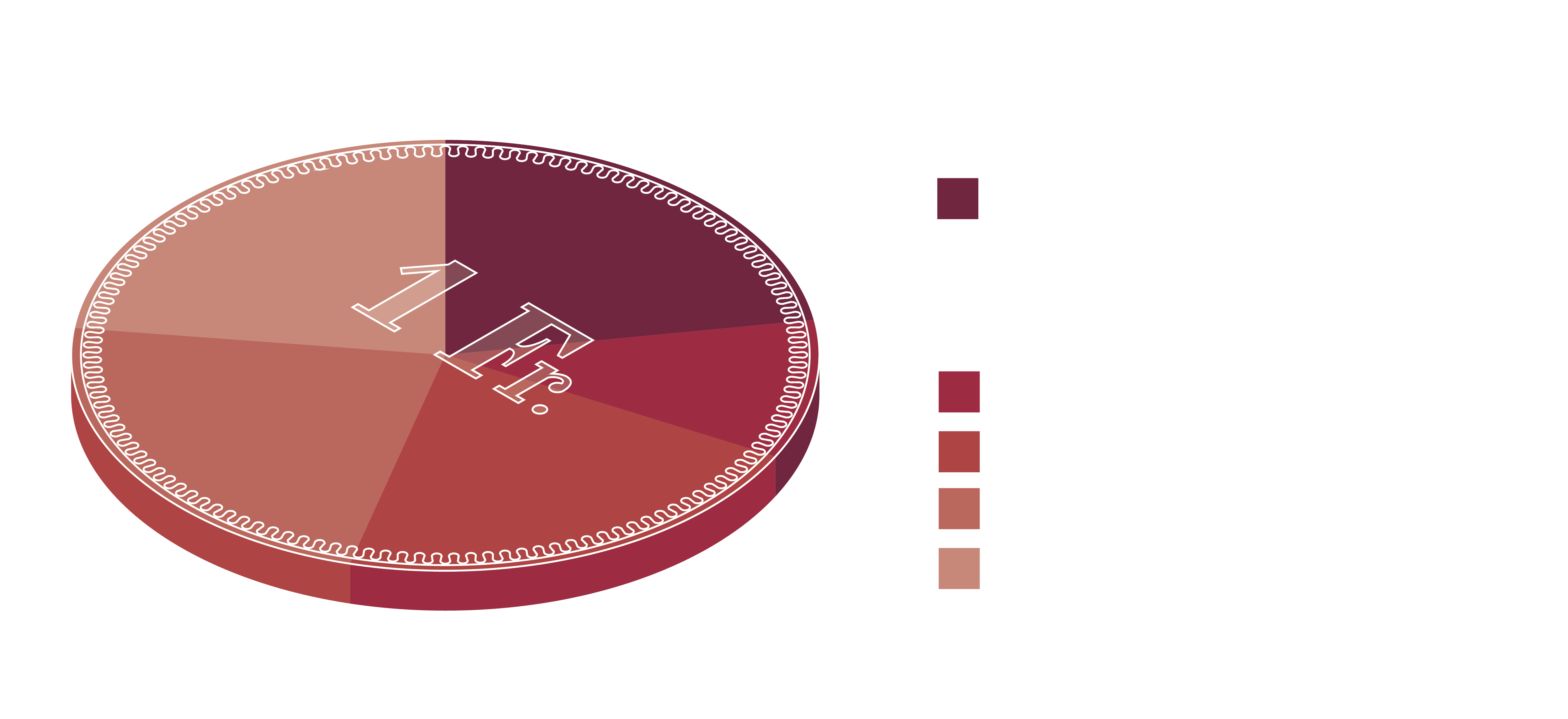

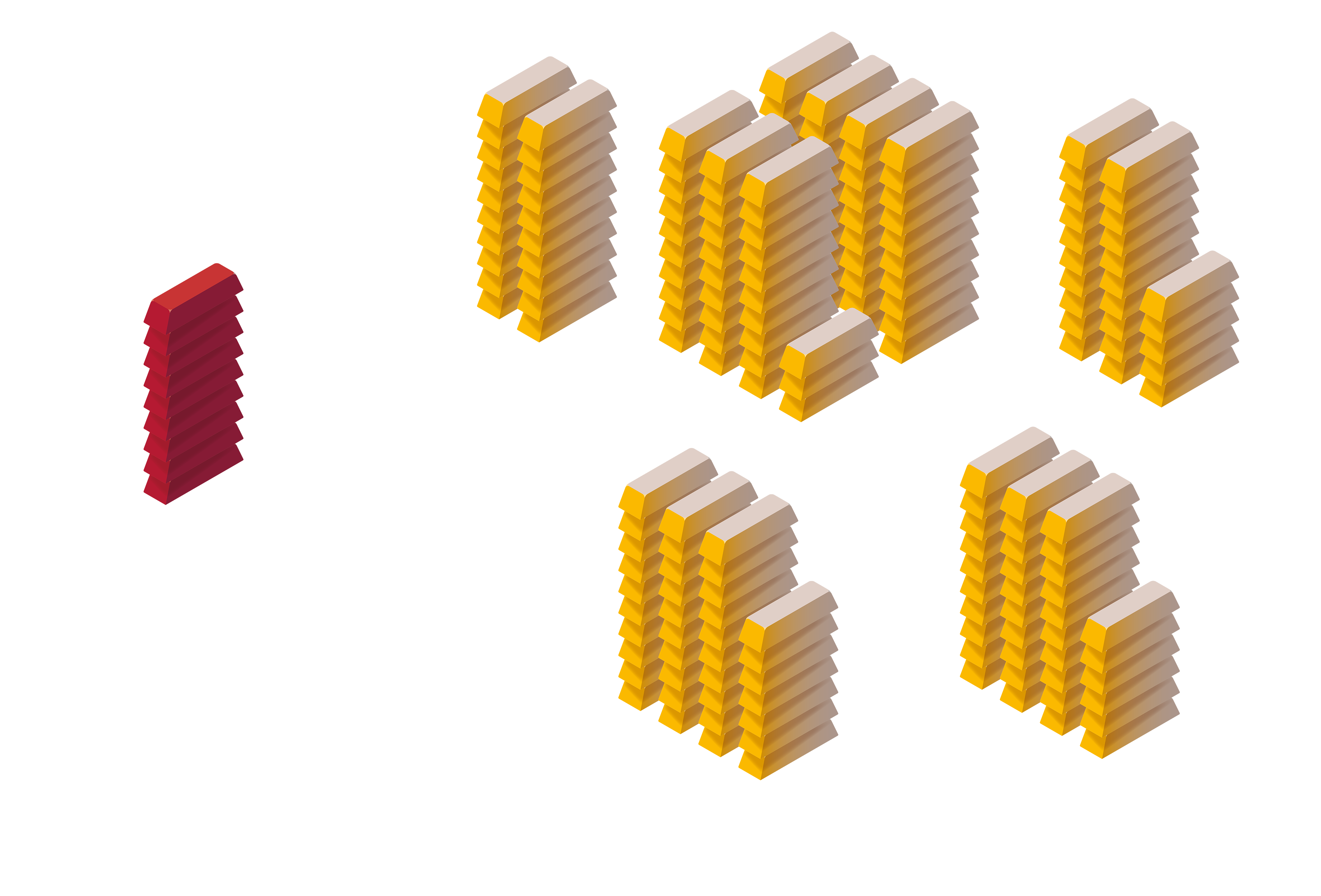

Source: WBG Zürich

The balance sheet of an average Zurich cooperative organization shows a surprisingly small amount of equity (red). The rest, even if it is funding that the cooperative controls, is considered debt (beige/gold). This debt breaks down as follows: the largest loans are provided by the ZKB and other banks, followed by loans from private entities including pension funds. When, as now, interest rates are at historic lows, all types of lenders consider lending to cooperative organizations to be a safe and low-risk endeavor. The smallest percentage of loans originate from the public sector. In addition, cooperatives operate their own savings banks and a renewal fund. (

Documents

Visualization: Monobloque

Source: Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

From the beginning of its involvement in housing in 1896, the public sector in Zurich has chosen not to lend directly to cooperatives. Rather, private entities like the ZKB (since 1902) and the City of Zurich Pension Fund (since 1992) have been obliged to do so, while the public sector insures them against loss. Because cooperatives, despite receiving preferential access to financing, are economically and fiscally independent actors in the real estate market, elected officials have been able to maintain that the city does not directly subsidize them. It is one reason cooperatives have had public support across the political spectrum.

Source: Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

Source: FGZ archives

The Familienheim-Genossenschaft Zürich (FGZ), a cooperative focused on providing homes to families with children, was among the first cooperatives to take advantage of the 1924 municipal resolution permitting cooperatives to access financing with only 6 percent equity as collateral. During the first two construction phases at Friesenberg in 1925–26 (of a total of 23 phases as of 2021), the FGZ built 144 rowhouses and apartments in a garden city layout. Today, the site’s future is highly contested. The FGZ would like to redevelop the site as a whole, arguing that renovation is too expensive. Preservationists counter that the design is unique and of high quality. They seek to prevent the demolition of at least the 1925–26 phases.

Plan courtesy of pool Architekten

Through a land deal between the City of Zurich and ABZ in 2011, the cooperative organization obtained some 24 000 m² of land in a new urban development near Zurich Airport. In 2015, following an architectural competition, the ABZ general assembly approved the development cost of 97.5 million Swiss francs to pursue the winning project. In two phases, 286 apartments, ranging from 1.5 to 8.5 rooms, were realized for a broad mix of 800 residents, bringing the total number of apartments operated by ABZ to over 5 000. A kindergarten, nursery and restaurants are located in the ground-floor areas. The open courtyards between the four buildings are connected by passages.

Photo: Sanna Kattenbeck

The Glattpark neighborhood beyond the city limits of Zurich consists mainly of private, for-profit development. The project for ABZ, designed by pool Architekten (first three building blocks in the foreground), is an exception. It articulates an urban facade toward the public square, and its courtyards are accessible to residents and the general public alike. In contrast, private developers tend to privatize the public space in their developments with individual gardens or glazed balconies.

Research: Nina Baisch, Bianca Matzek

6.

Land

The high percentage of cooperative land ownership in Zurich contributes to the city’s socio-spatial balance. Land is removed from speculation, curbing gentrification and keeping inner-city apartments affordable. Large, contiguous sites allow for the collective use of urban green spaces.

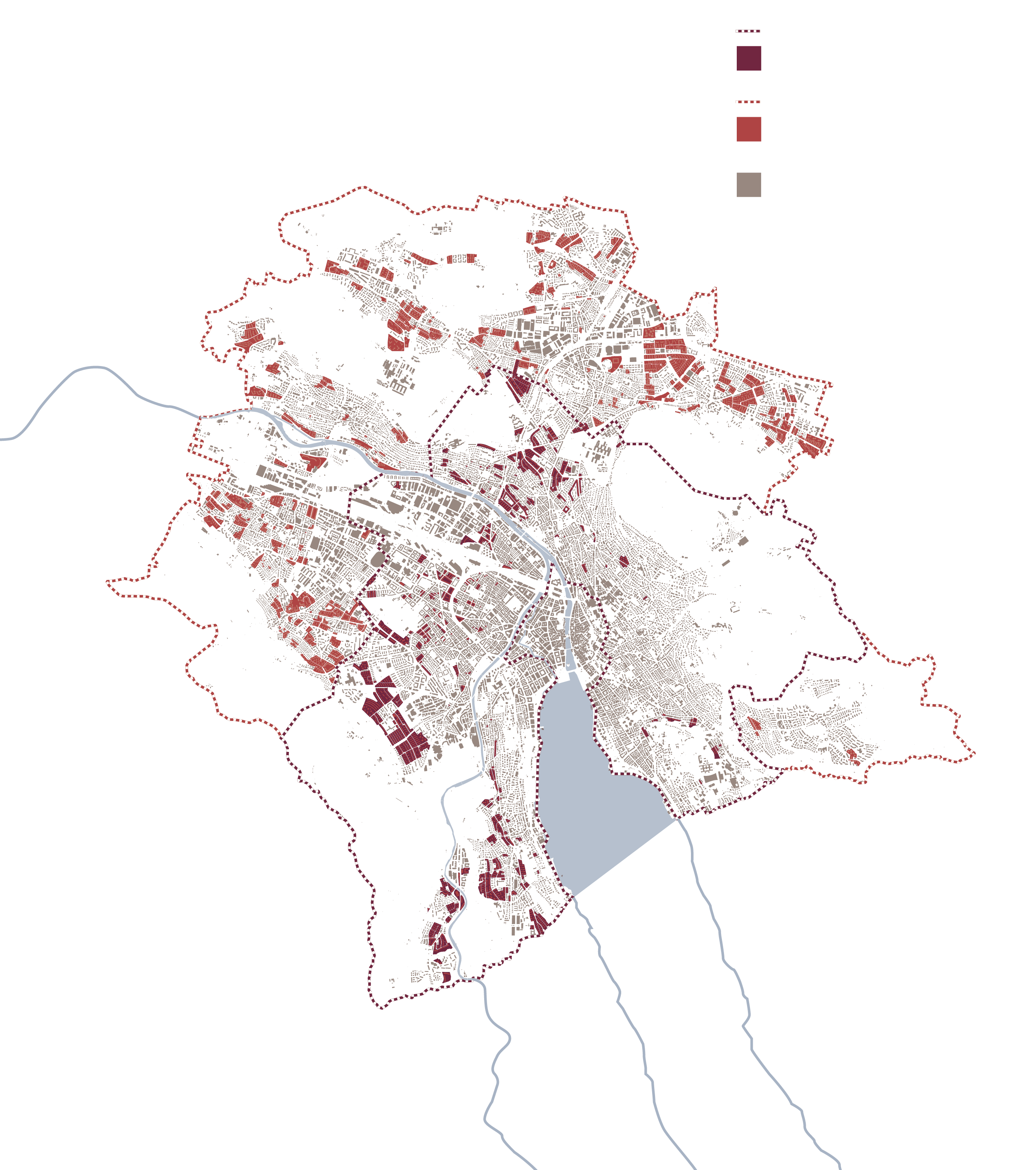

Agency

Cooperative organizations own around 9 percent of Zurich’s buildable land and 18 percent of the city’s housing stock. Owning entire neighborhoods is key to cooperatives’ resilient, long-term planning practices. Organizations can rehabilitate or redevelop their housing stock in phases over several decades. This sustainable occupancy policy allows lower-income groups to remain in place.

Visualization: Sanna Kattenbeck & Monobloque

Source: GIS-Browser Kanton Zürich

The majority of Zurich’s cooperative organizations acquired their land from the 1920s to the 1950s. Today’s low rents directly result from the low initial purchase price of the land, as the rent calculation is based on the initial price and not on the current market value.

Concurrently, that same land ownership guarantees cooperatives’ AAA credit rating precisely because the theoretical market value of the land has increased approximately a hundredfold since purchase. Cooperatives can finance redevelopment projects by rescheduling debt backed by land, even though the land is not for sale due to the cooperatives’ commitment to nonspeculation.

The garden city model of urban planning, premised on rejecting the individual parcel, best exemplifies the promise of collective land ownership. Under cooperative stewardship, generous collective landscapes and playgrounds are accessible to the public and enjoyed by residents.

Instruments

Outright Ownership

Outright ownership of land is a legal construct for assigning rights and responsibilities of individual or juridical persons to a piece of property, defined as a part of the earth’s surface and registered in a deed. The collective private property of cooperative organizations is a hybrid of ownership and rental models: residents are both collective shareholders and individual renters.

Leasehold of Municipal Land

A leasehold (Baurecht) is a legal arrangement by which the land owner grants rights to use of land against payment of rent. In Zurich, leaseholds of municipal land are usually granted for 62 years, extendable by 30 years. For the municipality, this ensures long-term control of urban development. For cooperative organizations, it ensures access to buildable land that today has become expensive and virtually impossible to come by, even as money is cheap.

Documents

Source: Camille Martin, Hans Bernoulli. Städtebau in der Schweiz. Grundlagen. Zurich:

Fretz & Wasmuth, 1929

The land owned by the City of Zurich includes not only land in residential areas but roads, infrastructure and forest. From the turn of the twentieth century onward, the City of Zurich has supported cooperatives through a policy of land reserves, possible because of low land prices. Between the urban expansions of 1893 and 1934, the share of land owned by the municipality (excluding streets and squares) rose from one-eighth to over one-third of the total urban area. Cooperative organizations had preferential access to this land, either through large plots or favorable prices. Cooperatives also benefited from the urban expansion of 1934 because it turned cheap agricultural land into buildable sites with amenities and infrastructure. In the 1950s, the City of Zurich halted the sale of municipal land. From 1965 onward, it systematically granted leaseholds.

Source: Stadtarchiv Zürich

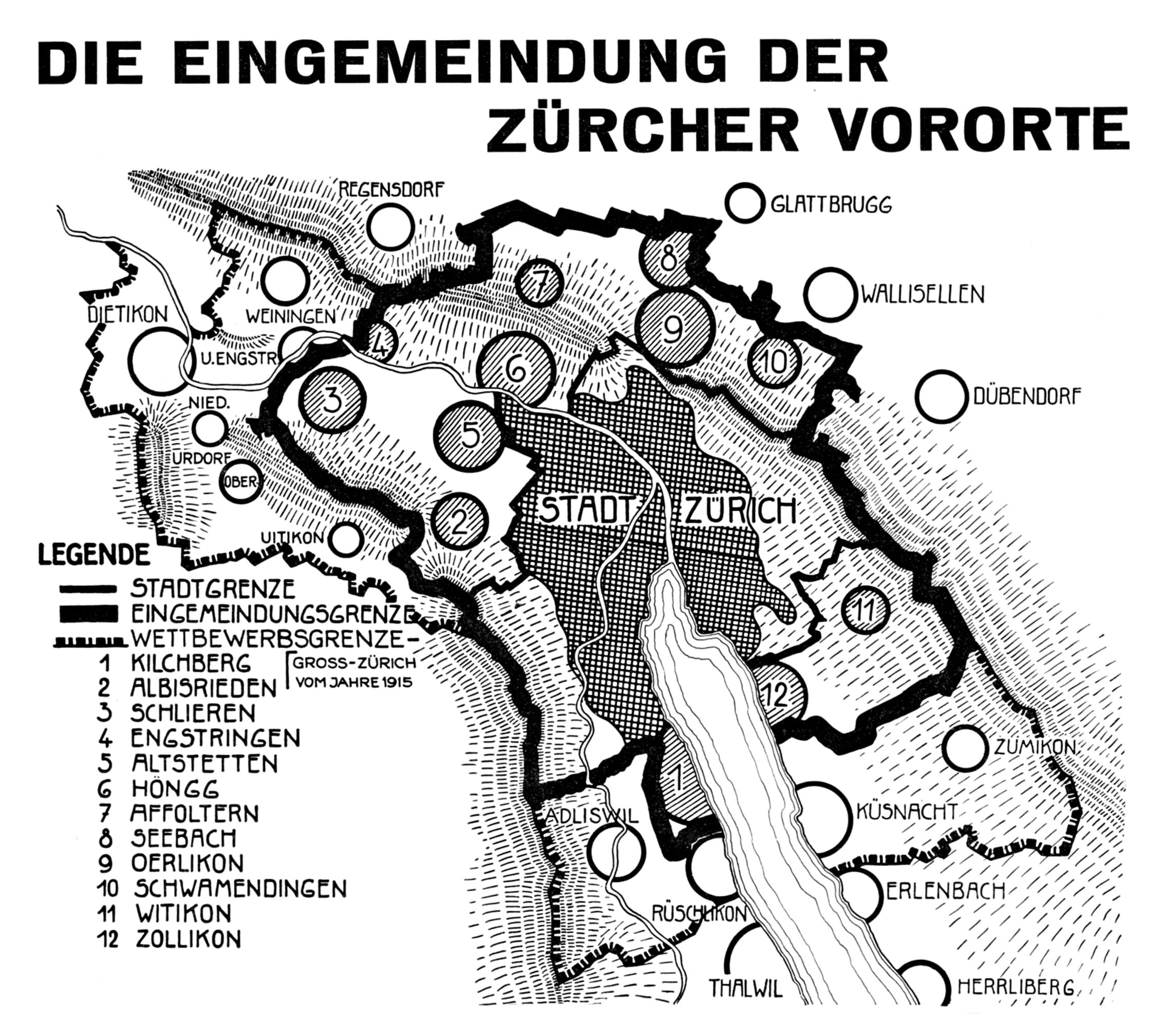

Source: Aktionskomitee für die Eingemeindung. Für die Eingemeindung der Zürcher Vororte. Zurich, 1929

Better urban design and bus service were used to make the case for incorporating neighboring towns and villages into the city of Zurich. A referendum to approve this was rejected by voters, but a second urban expansion was nonetheless put in place in 1934.

Architect: City Architect Albert Heinrich Steiner

Source: Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

Photo: Werner Friedli/Bildarchiv der ETH-Bibliothek

Visualization: Monobloque

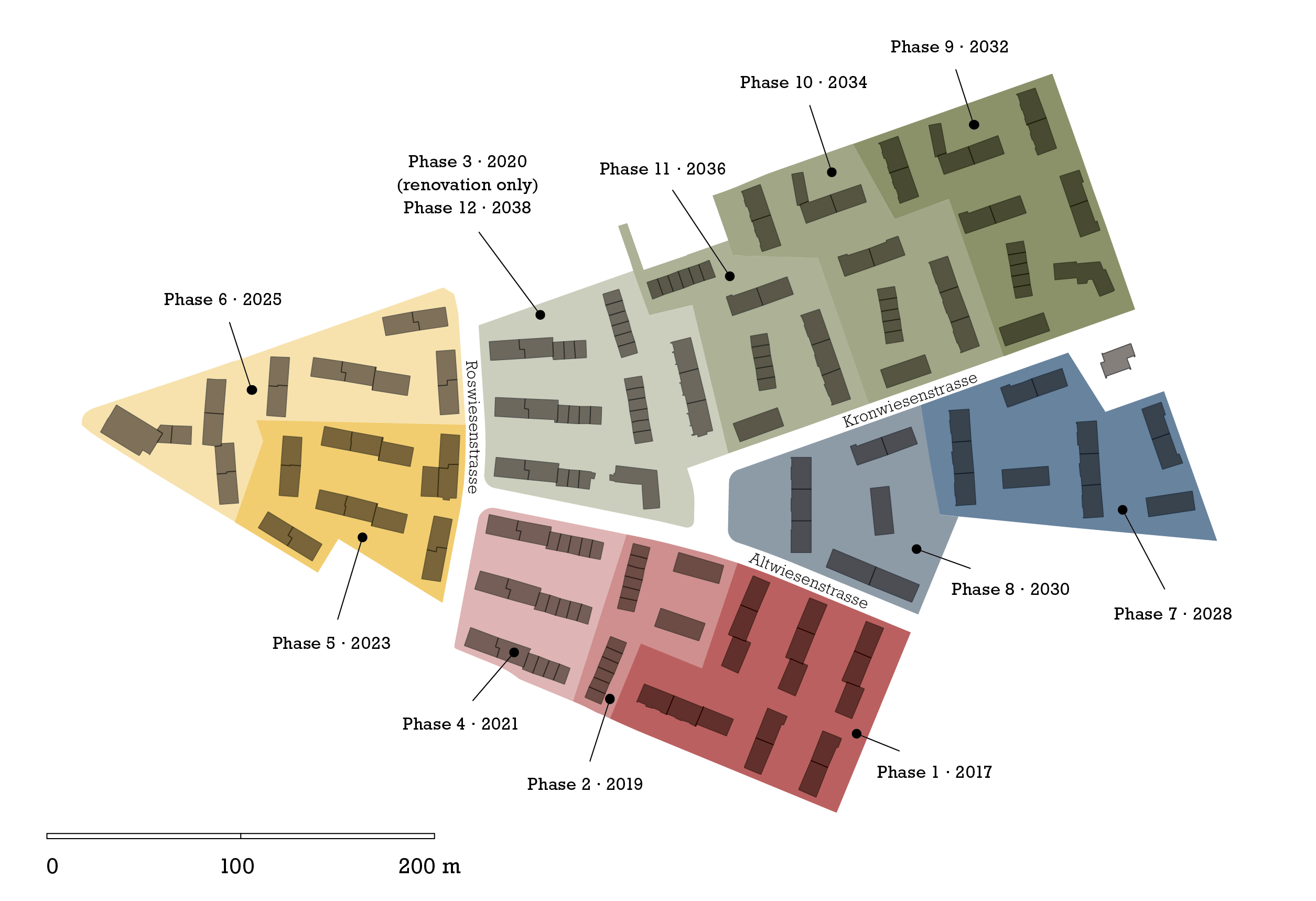

Source: BGZ masterplan, 2012

The size and long-standing ownership of land in Schwamendingen allows Baugenossenschaft Glattal Zürich (BGZ), a cooperative organization founded in 1942, to pursue a phased renewal of its housing stock over 23 years.

Research: Anna Derriks, Sanna Kattenbeck

7.

Zoning

The City of Zurich uses its zoning code to give cooperatives access to buildable land and to allow forms of urban design that support cooperatives’ collective use of interior and exterior spaces.

Agency

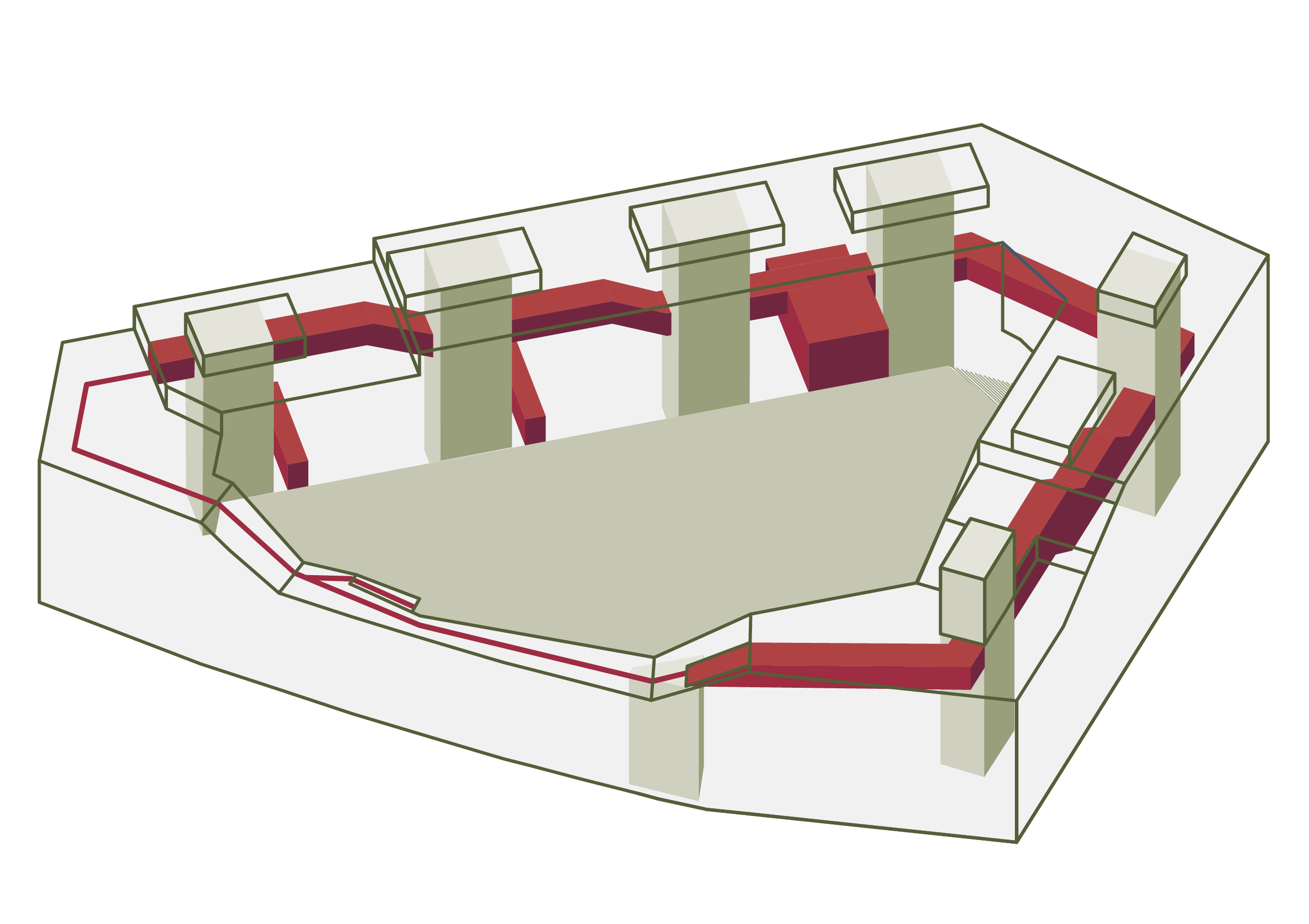

In Zurich, the floor area of collectively used spaces does not count toward the floor area ratio (FAR). This encourages developers to locate these spaces on the ground floor or in other attractive places within the building. Cooperative organizations make particular use of this rule to create inviting, multiuse shared spaces.

The Planned Development Area promotes forms of urban design that privilege collective open space over individual gardens since allowable FAR can be distributed on the site more coherently than in parcel-based planning. Since cooperatives tend to build more and smaller dwellings than private developers, shared courtyards or landscaped terraces acquire key importance for design, use and maintenance.

Since 1995, the Planned Development Area has been the decisive instrument to promote densification as it allows building to a higher density than on individual parcels. For cooperatives, however, it is also a tool to preserve the relatively low-rise neighborhood identity of the garden city. Because of their commitment to nonspeculation, cooperatives rarely maximize the legally permitted building volume in redevelopment projects.

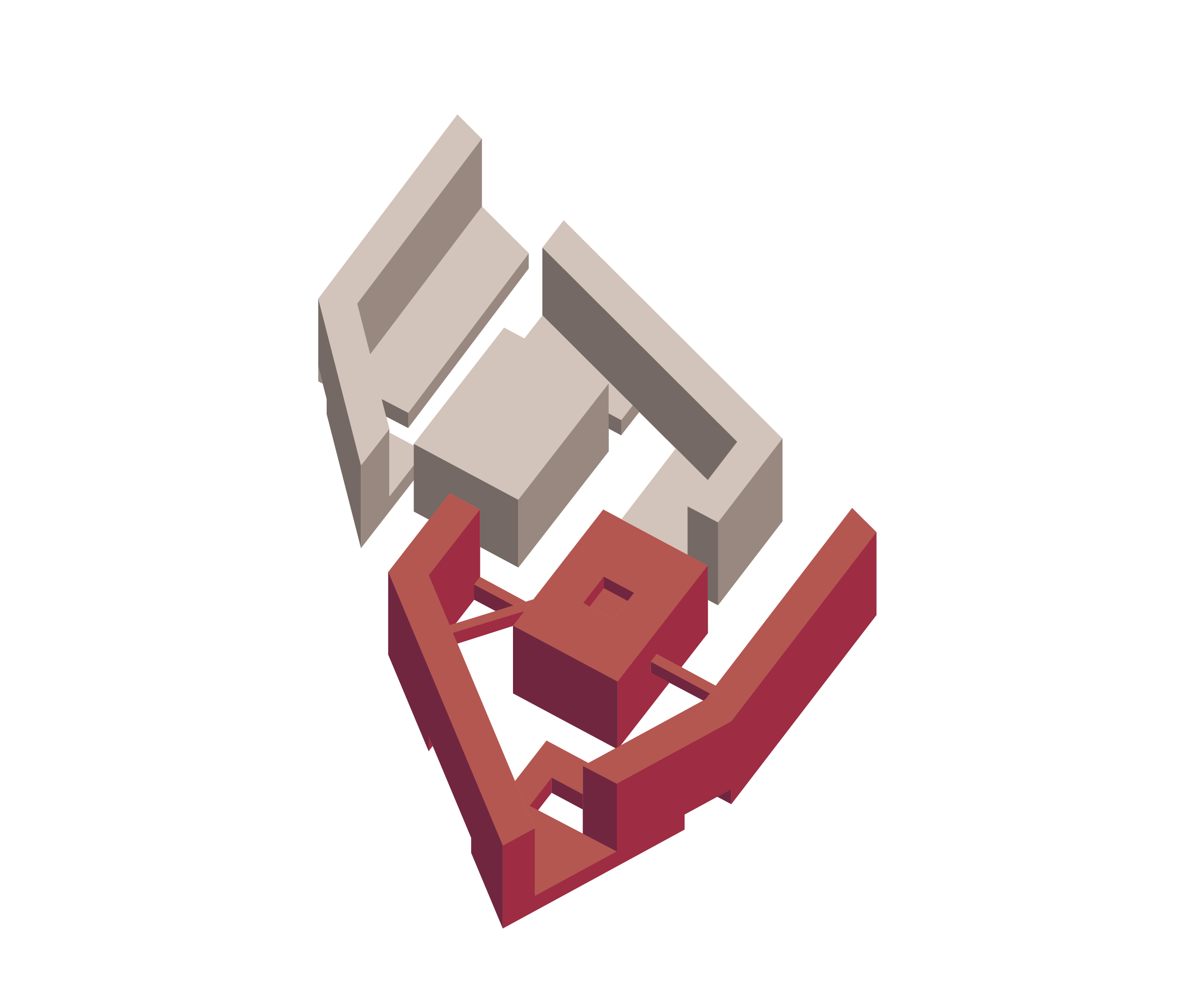

Visualizations: Sarah Hummel, Olga Rausch & Monobloque

Instruments

Floor Area Ratio

Floor area ratio or FAR (Ausnützungsziffer) is a relational measure of building density, defined as the ratio of a building’s total floor area to the area of the parcel upon which it is built. A unique aspect of Zurich’s FAR is that ancillary spaces not used for permanent occupancy are excluded from the calculation if they enhance overall livability.

Planned Development Area

The Planned Development Area (Arealüberbauung) applies to properties that are at least 6 000 m2 in size. It allows, as of right, higher density than on individual parcels in the same zoning district and flexible placement of the allowable building volume, but projects must comply with energy-efficiency and design standards. Holding an architectural competition is one way to demonstrate this compliance.

Appreciation Tax and Special Area Plan

The appreciation tax (Mehrwertabgabe) is a municipal tax of 20–40 percent levied once on the appreciation of land values resulting from zoning or public investment. Since 2009, the City of Zurich used the tax in conjunction with the Special Area Plan (Gestaltungsplan), filed to apply for the rezoning of large sites, where the tax is paid by allocating land to cooperative housing.

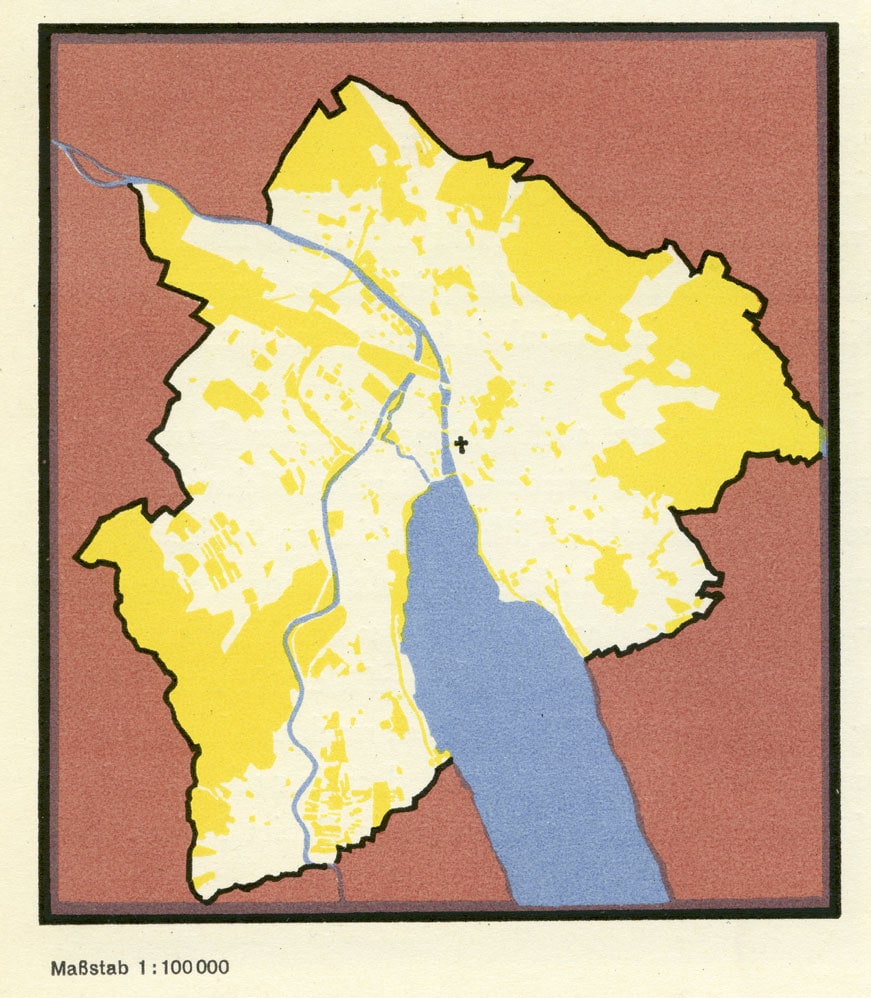

Visualization: Sarah Hummel, Olga Rausch & Monobloque

Source: Amt für Städtebau. Gerechter. Die Entwicklung der Bau- und Zonenordnung der Stadt Zürich. Zurich, 2013

Documents

Photo: Verena Eggmann/Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv (F 5037-Fx-0005)

Ursula Koch played a decisive role in shaping Zurich’s urban development in favor of cooperatives. The controversial zoning code of 1992, launched by her office, promoted affordable, high-quality and family-friendly housing despite the lobbying of investors who sought to strengthen Zurich’s finance and service industries by creating new office space.

The stand-off between the canton’s conservative government and the city’s social-democratic administration ended in compromise in 1999, when the zoning code was revised to limit the rezoning of former industrial areas for commercial use but continued to allow for higher densities. The 1999 revision also introduced other aspects important for cooperatives today: it formalized various participatory processes in planning and created access to land via the Special Area Plan, in conjunction with the appreciation tax.

Source: Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv (F 5107-Na-07-155-008)

In the 1990s, the zoning code became a lightning rod for those questioning who ought to benefit from higher-density development, especially on former inner-city industrial sites: for-profit developers of office buildings or nonprofit developers of housing for families? The centrality of these debates is reflected in the increasing frequency of zoning code revisions: every fifteen years after 1946 and every three to four years in the 1990s.

Source: Amt für Städtebau. Teilrevision der Bau- und Zonenordnung. BZO 2014. Erläuterungsbericht. Zurich, 2014

Since its first zoning code was approved in 1946, the City of Zurich has used the Planned Development Area to support cooperative housing. Known as Comprehensive Development (Gesamtüberbauung) in the 1946 zoning code, the tool facilitated modern, low-density Siedlungen. With the 1963 revision of the zoning code, the tool was renamed Planned Development Area (Arealüberbauung), and was adjusted to encourage new development at higher densities. In the 1992 revision, the allowances for densification were further increased with the goal encouraging redevelopment of existing projects, as shown in the diagram above.

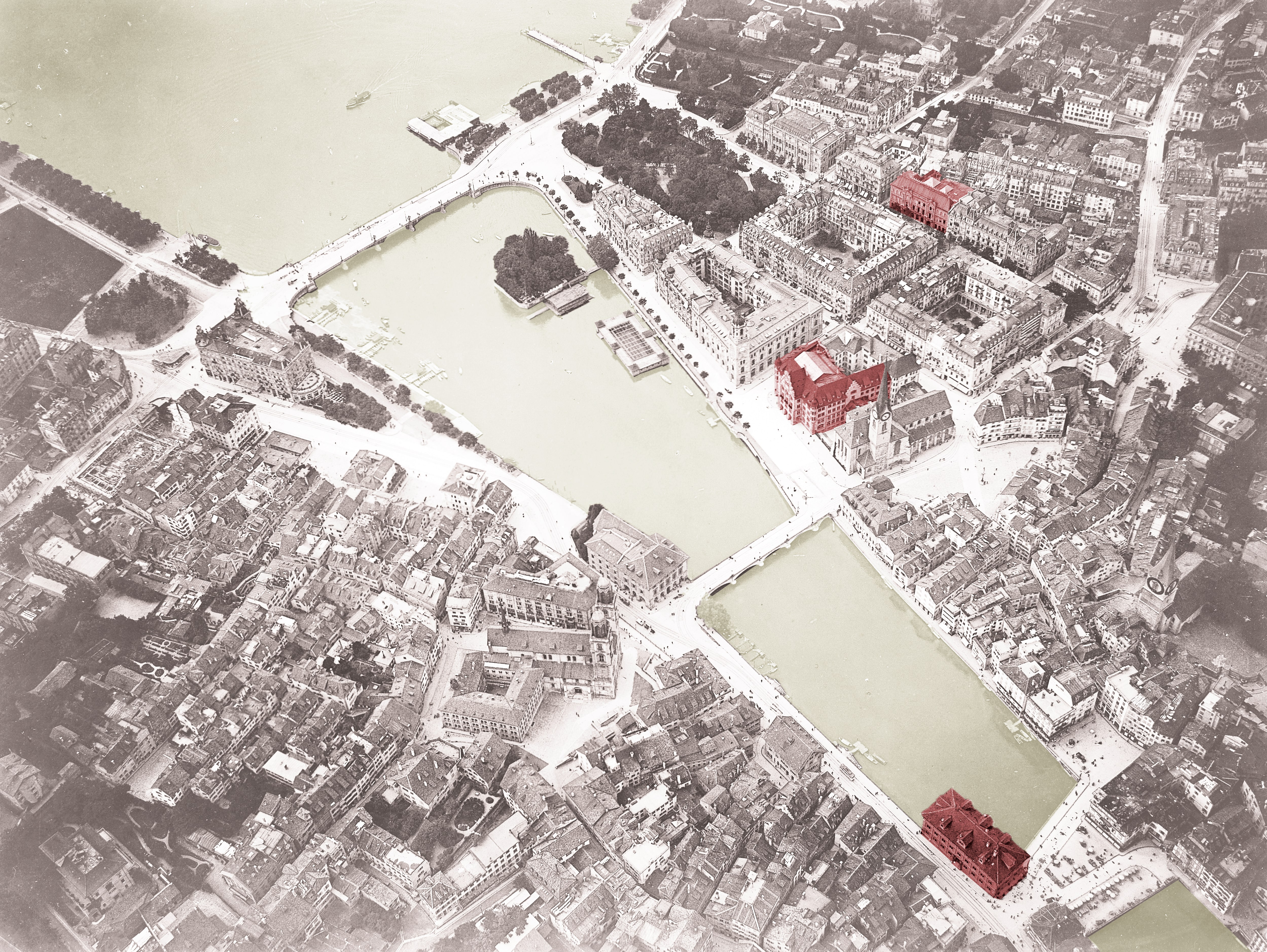

Photo: Swissair/Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

Prior to the promulgation of the 1946 zoning code and the Planned Development Area, garden city developments like Entlisberg were possible only through variances to existing regulations.

Photo: Juliet Haller/Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

Parts of the original Siedlung were demolished and redeveloped to make room for a denser development under the premises of a Planned Development Area. The flexibility of the Planned Development Area allowed preserving the openness of the garden city in the Entlisberg redevelopment even as the density increased by almost 50 percent. Meier Hug Architekten conceived of the new, collectively used longitudinal courtyard space as a “machine for collective life” to transcend the modernist machine for living.

Photo: Roman Keller, Zurich

Research: Sarah Hummel, Olga Rausch

8.

The Competition

An architectural competition aligns the users, the client, the municipality and the architect behind a common imaginary of the future living environment articulated in the architectural project. A transparent and binding process, it promotes public understanding and trust in what design can achieve.

Photo: Anna Derriks

From writing the brief to the jury process, competitions build knowledge and commitment among residents, cooperative organizations and architects alike. Cooperatives must think carefully about what they want, so that architects can be given a detailed and challenging competition brief. In the case of the Kalkbreite complex, the competition process was essential for the new organization to establish legitimacy and develop a shared vision of its future.

Because of the binding nature of the competition process, the winner receives a commission, no matter how experimental or new the design is. Competitions are therefore not only intellectually stimulating for architects but provide potential financial rewards that justify the risk of investing 1 000-plus hours of work.

Architectural competitions make innovation in housing economically profitable and socially acceptable. A cooperative organization might invest 300 000 Swiss francs or more in the process because residents and management will draw long-lasting benefits from a proposal that has been vetted by all.

Instruments

Competition Brief