8. The Competition

An architectural competition aligns the users, the client, the municipality and the architect behind a common imaginary of the future living environment articulated in the architectural project. A transparent and binding process, it promotes public understanding and trust in what design can achieve.

Agency

Instruments

History

Documents

Agency

Agency

From writing the brief to the jury process, competitions build knowledge and commitment among residents, cooperative organizations and architects alike. Cooperatives must think carefully about what they want, so that architects can be given a detailed and challenging competition brief. In the case of the Kalkbreite complex, the competition process was essential for the new organization to establish legitimacy and develop a shared vision of its future.

Because of the binding nature of the competition process, the winner receives a commission, no matter how experimental or new the design is. Competitions are therefore not only intellectually stimulating for architects but provide potential financial rewards that justify the risk of investing 1 000-plus hours of work.

Architectural competitions make innovation in housing economically profitable and socially acceptable. A cooperative organization might invest 300 000 Swiss francs or more in the process because residents and management will draw long-lasting benefits from a proposal that has been vetted by all.

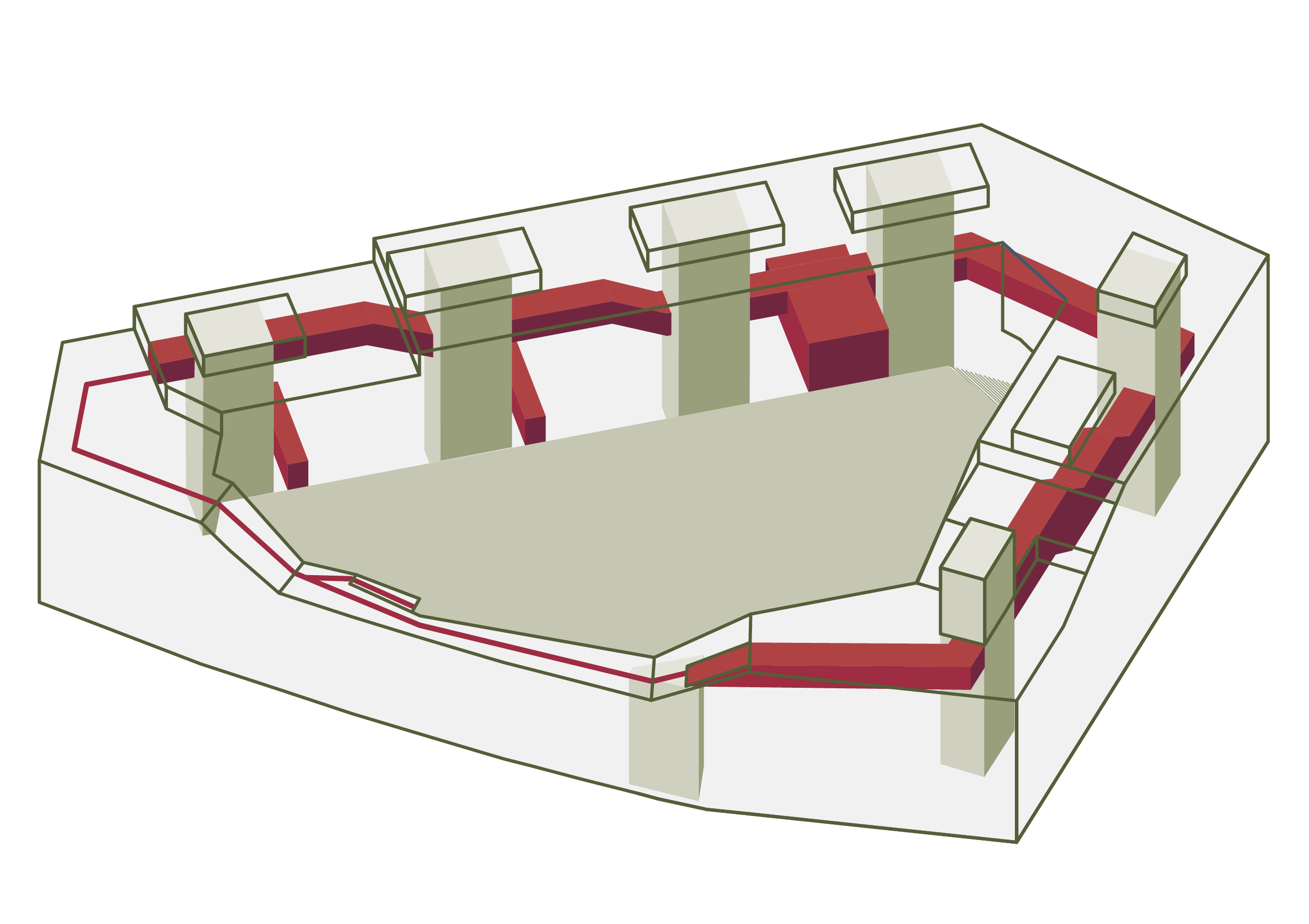

Source: Müller Sigrist Architekten

The interior street (rue intérieure) connects the versatile program across several floors and culminates at both ends on the roof terrace.

Instruments

Instruments

Competition Brief

To sponsor a competition, cooperative organizations must identify the goals of the new complex in the form of a competition brief. To develop alternatives to societal norms, organizations often launch elaborate participatory processes involving the various stakeholders in the project. Because they know their residents well, cooperatives can respond more precisely to residents’ current and future needs than private investors could.

Competition for Land Lease

Since the late 1980s, the City of Zurich has held competitions among cooperative and private developers for the leasehold of municipal land. Since 1991, leasehold contracts have required leasehold winners to organize an architectural competition to ensure the urban and architectural quality of the site’s future development.

Architectural Competition

The goal of an architectural competition is to find the best proposal and avoid cronyism in awarding contracts. The principles of competition were developed in 1877 by the Swiss Association of Engineers and Architects (SIA) and are still valid today: a binding project brief, a jury with a majority of building professionals, prize money commensurate to the effort, and a public exhibition of all submitted works.

History

History

A few years after becoming the head of Zurich’s Building Department in 1986, the Social Democrat Ursula Koch issued new guidelines for the city’s urban policy. From then on, buildings on city-owned land were to be of outstanding design quality. The goal was to make Zurich an attractive place for families to live. From this moment onward, each competition for the leasehold of municipal land obliged the winning developer to sponsor an architectural competition.

Cooperatives became a key beneficiary of this policy. By the 1980s, many were managing existing complexes but were no longer building new ones. By expanding competitions for leaseholds of municipal land and financially supporting architectural competitions, the city persuaded cooperatives to become active developers again—and not only of new land but through densification. Together, leaseholds for municipal land and architectural competitions transformed cooperatives from stewards to innovators. The public jury procedure triggered public debate about submitted designs and increased confidence in the transparency of the process.

Today, the architectural competition has been voluntarily adopted by the majority of Zurich housing developers, whether nonprofit or for-profit.

Documents

Documents

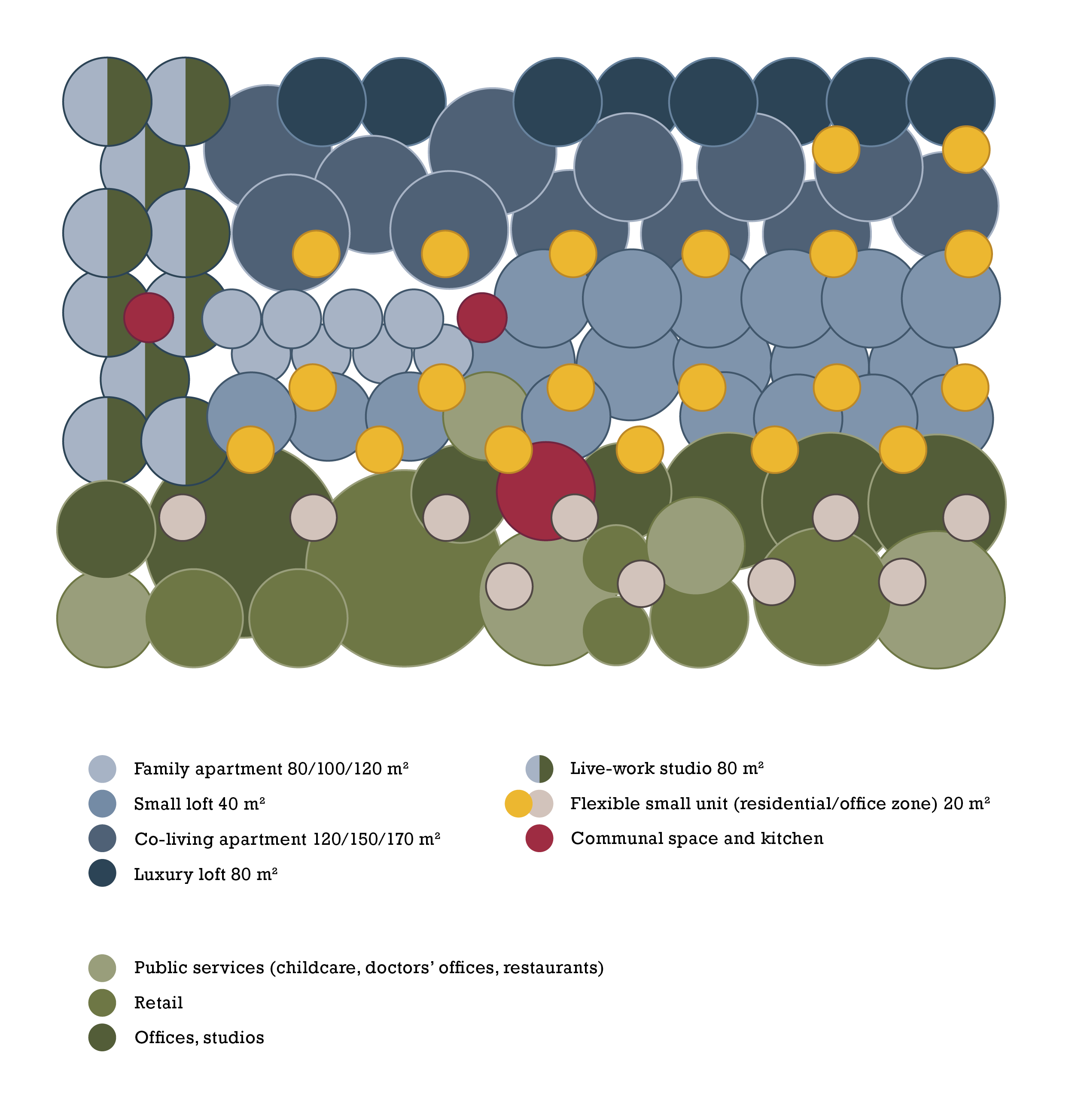

Visualization: Monobloque

Source: Genossenschaft Kalkbreite

In 2007, the Kalkbreite Association founded a cooperative organization. It won the competition for the land lease on the basis of its daring but precise building program: 5 000 m² of small-scale commercial and business space with workplaces for 200 people, coupled with 7 500 m² of living space for 250 residents.

Housing was also determined by mix, through quotas for old and young, Swiss and non-Swiss residents, as well as for new apartment types (e.g., cluster apartments and rooms for short-term living).

Finally, the Kalkbreite program called for a new relationship between private and collective spaces: only 30 m² instead of the Zurich average of 42 m² per resident, counterbalanced with 600 m² of shared space in addition to the courtyard with children’s playground, access zones, communal kitchens, a library, guest rooms and a central laundry room.

Alongside a plaster model of the site and urban context, a 57-page document with technical details and noise pollution studies, the competition brief included eight postcards with so-called use cases. Members of the cooperative had taken snapshots of their future living situation on the project site, an inner-city tram depot. Architects were asked to respond to these stories with their design.

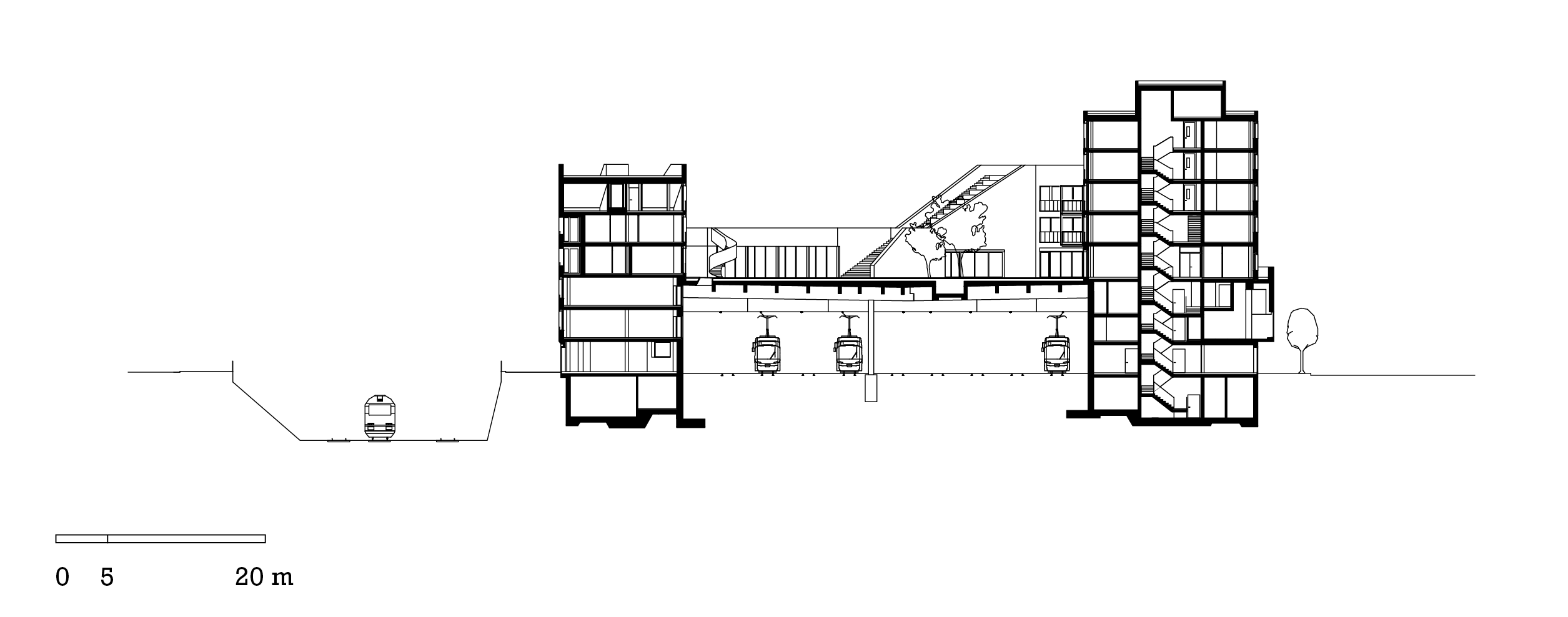

Plan courtesy of Müller Sigrist Architekten

In 2008 the project design by Müller Sigrist Architect won the open, international, anonymous architectural competition for which 54 projects were submitted. A polygonal courtyard building vertically separates residential and commercial zones and places a publicly accessible courtyard on the roof of the tram depot.

Research: Sébastien El Idrissi, Kana Ueda