5. Debt

Around 80 percent of the value of Zurich’s cooperatives is debt. Private and public-sector lenders alike consider cooperatives to be reliable borrowers and to provide lucrative investment opportunities, a status materialized through architecture that is built to last.

Agency

Instruments

Documents

Agency

Agency

For Zurich cooperatives and their lenders, debt means security. Debt is not seen as a short-term, high-risk endeavor but rather is understood as a long-term commitment. As a result, architecture is built to last for generations. This plays out in the choice of high-quality building materials, whether in façades, floors or hardware. Siedlung Friesenberg, for example, has been in use for close to a century.

For lenders, cooperatives provide lucrative investment opportunities. Zurich’s minimal vacancy rate of 0.15 percent ensures that cooperative apartments, offering high use value at low cost, will never go unrented. For cooperatives, a choice of lenders allows debt to be rescheduled at favorable rates. In turn, this gives cooperatives the leeway to pursue nonstandard architectural solutions.

For cooperatives, servicing long-term debt goes hand in hand with a willingness to take risks on endeavors that may only play out in the long term. This includes developing large-scale projects in the urban periphery and embracing urban design to encourage the use of open space by diverse actors, such as the Glattpark development near Zurich Airport.

Instruments

Instruments

Loans from Conventional Banks

Most of the debt owed by Zurich cooperatives was obtained from banks at conventional interest rates. These first mortgages typically cover 60–80 percent of development costs. The Zurich Cantonal Bank (ZKB), a private bank backed by the Canton of Zurich, has had a legal obligation to lend to cooperatives since 1902. (

Loans from Pension Funds and Other Private Entities

Since 1992, most cooperatives have also obtained second mortgages, which fund 14–34 percent of development costs, from the City of Zurich Pension Fund. This is a private institution whose lending to cooperatives, however, is backed by the City of Zurich. Additional long- and short-term loans are made by a variety of private individuals and institutions.

Loans from the Public Sector

The public sector, whether at the municipal, cantonal or federal level, provides few direct loans to cooperatives. The indirect mechanisms for low-interest loans include the Swiss Bond Issuance Cooperative (Emissionszentrale), which since 1990 has enabled cooperatives to refinance loans upon completion of a project. A revolving fund (fonds de roulement) has been lending up to 50 000 Swiss francs per dwelling unit since 2007.

Source: WBG Zürich

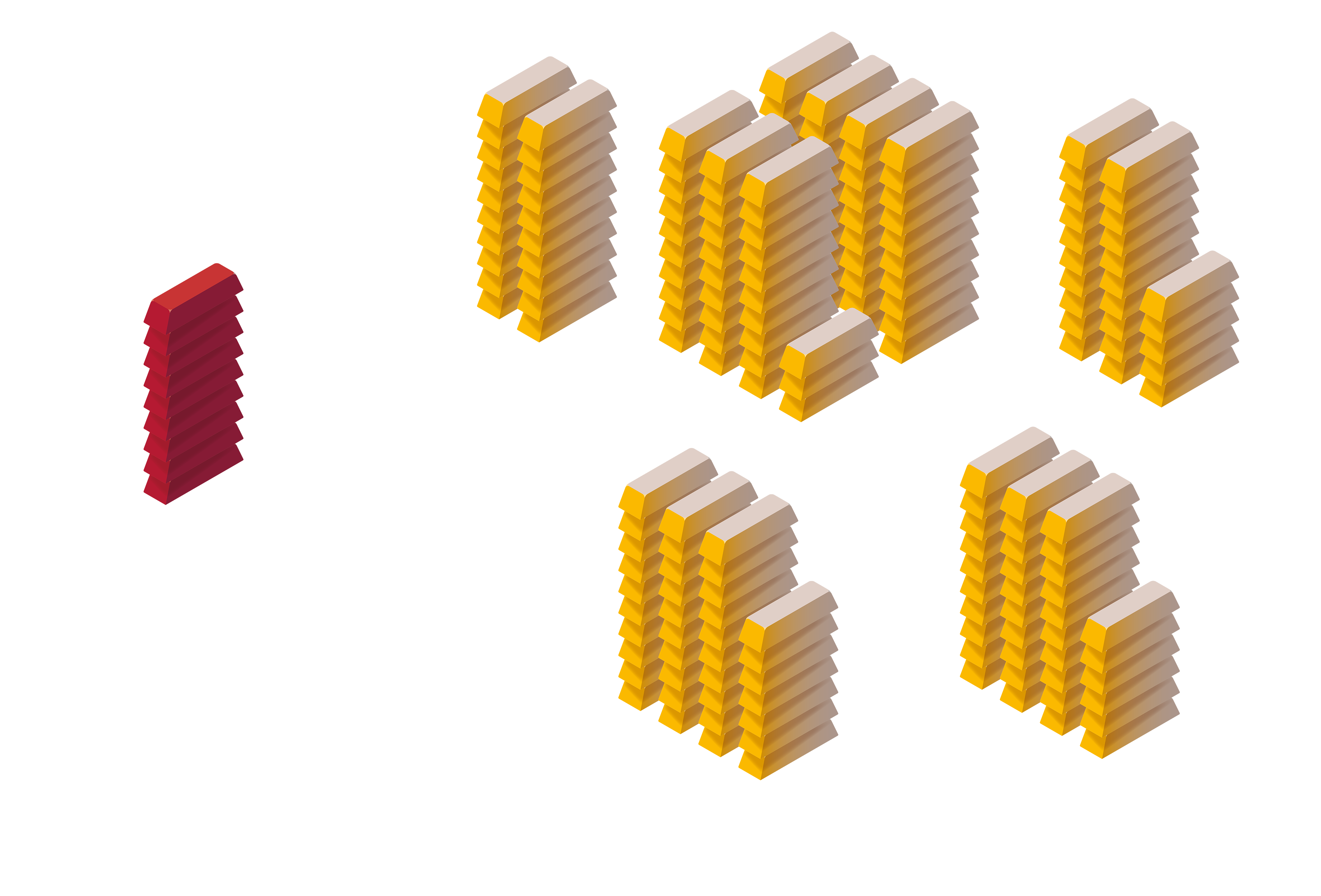

The balance sheet of an average Zurich cooperative organization shows a surprisingly small amount of equity (red). The rest, even if it is funding that the cooperative controls, is considered debt (beige/gold). This debt breaks down as follows: the largest loans are provided by the ZKB and other banks, followed by loans from private entities including pension funds. When, as now, interest rates are at historic lows, all types of lenders consider lending to cooperative organizations to be a safe and low-risk endeavor. The smallest percentage of loans originate from the public sector. In addition, cooperatives operate their own savings banks and a renewal fund. (

Documents

Documents

Visualization: Monobloque

Source: Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

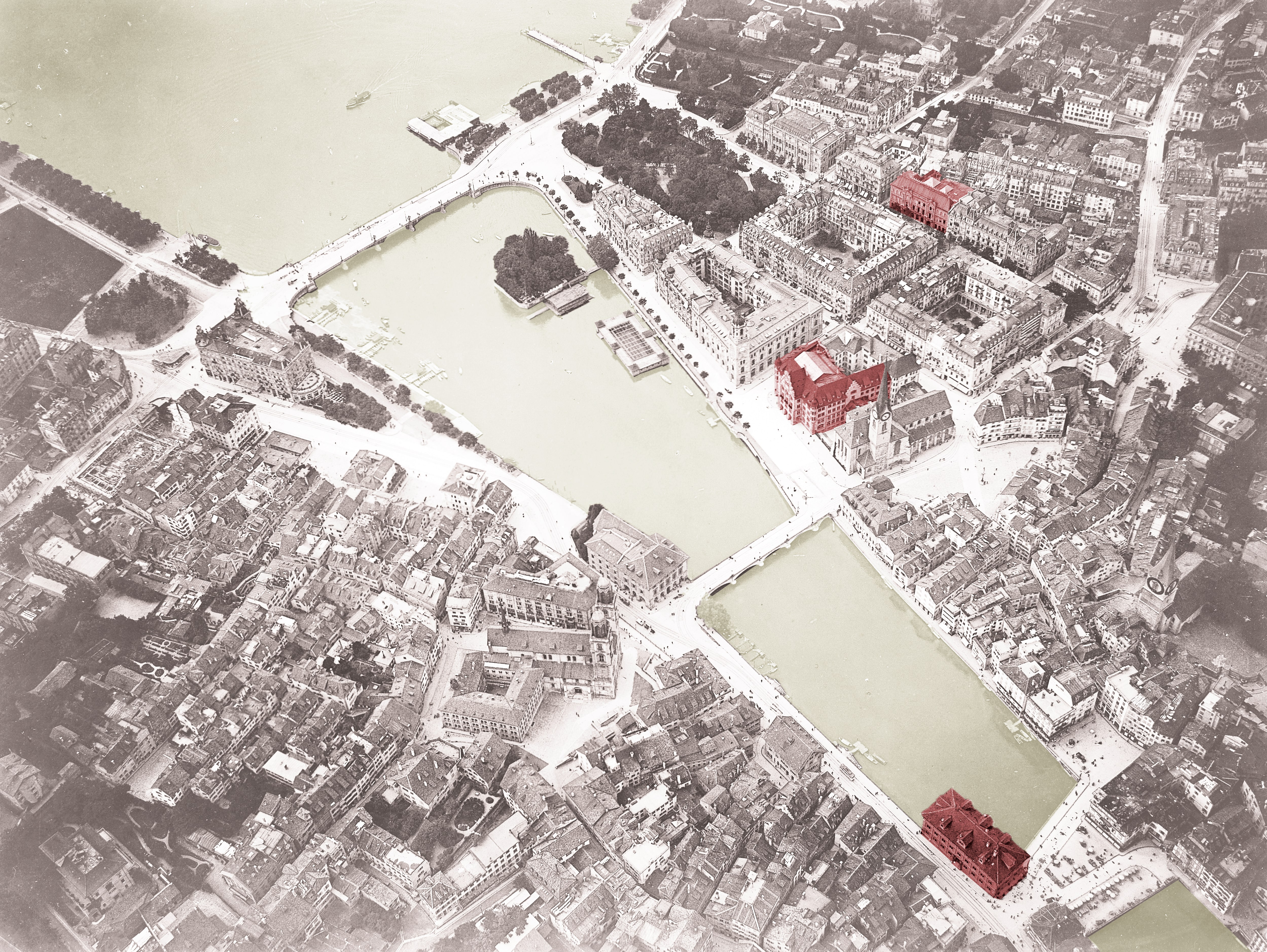

From the beginning of its involvement in housing in 1896, the public sector in Zurich has chosen not to lend directly to cooperatives. Rather, private entities like the ZKB (since 1902) and the City of Zurich Pension Fund (since 1992) have been obliged to do so, while the public sector insures them against loss. Because cooperatives, despite receiving preferential access to financing, are economically and fiscally independent actors in the real estate market, elected officials have been able to maintain that the city does not directly subsidize them. It is one reason cooperatives have had public support across the political spectrum.

Source: Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

Source: Baugeschichtliches Archiv der Stadt Zürich

The Familienheim-Genossenschaft Zürich (FGZ), a cooperative focused on providing homes to families with children, was among the first cooperatives to take advantage of the 1924 municipal resolution permitting cooperatives to access financing with only 6 percent equity as collateral. During the first two construction phases at Friesenberg in 1925–26 (of a total of 23 phases as of 2021), the FGZ built 144 rowhouses and apartments in a garden city layout. Today, the site’s future is highly contested. The FGZ would like to redevelop the site as a whole, arguing that renovation is too expensive. Preservationists counter that the design is unique and of high quality. They seek to prevent the demolition of at least the 1925–26 phases.

Plan courtesy of pool Architekten

Through a land deal between the City of Zurich and ABZ in 2011, the cooperative organization obtained some 24 000 m² of land in a new urban development near Zurich Airport. In 2015, following an architectural competition, the ABZ general assembly approved the development cost of 97.5 million Swiss francs to pursue the winning project. In two phases, 286 apartments, ranging from 1.5 to 8.5 rooms, were realized for a broad mix of 800 residents, bringing the total number of apartments operated by ABZ to over 5 000. A kindergarten, nursery and restaurants are located in the ground-floor areas. The open courtyards between the four buildings are connected by passages.

Photo: Sanna Kattenbeck

The Glattpark neighborhood beyond the city limits of Zurich consists mainly of private, for-profit development. The project for ABZ, designed by pool Architekten (first three building blocks in the foreground), is an exception. It articulates an urban facade toward the public square, and its courtyards are accessible to residents and the general public alike. In contrast, private developers tend to privatize the public space in their developments with individual gardens or glazed balconies.

Research: Nina Baisch, Bianca Matzek